By Alex Jones

100 YEARS ago, a small Scottish harbourtown witnessed the single greatest loss of warships in history. On the morning of 21 June, 1919, 74 German warships were interned at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, the anchorage for the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet throughout the First World War. By the end of the day, more than 50 of the German High Seas Fleet were resting on the seabed. The carnage was not inflicted by any enemy but rather by a thwarted German commander who refused to allow his ships to become the spoils of war.

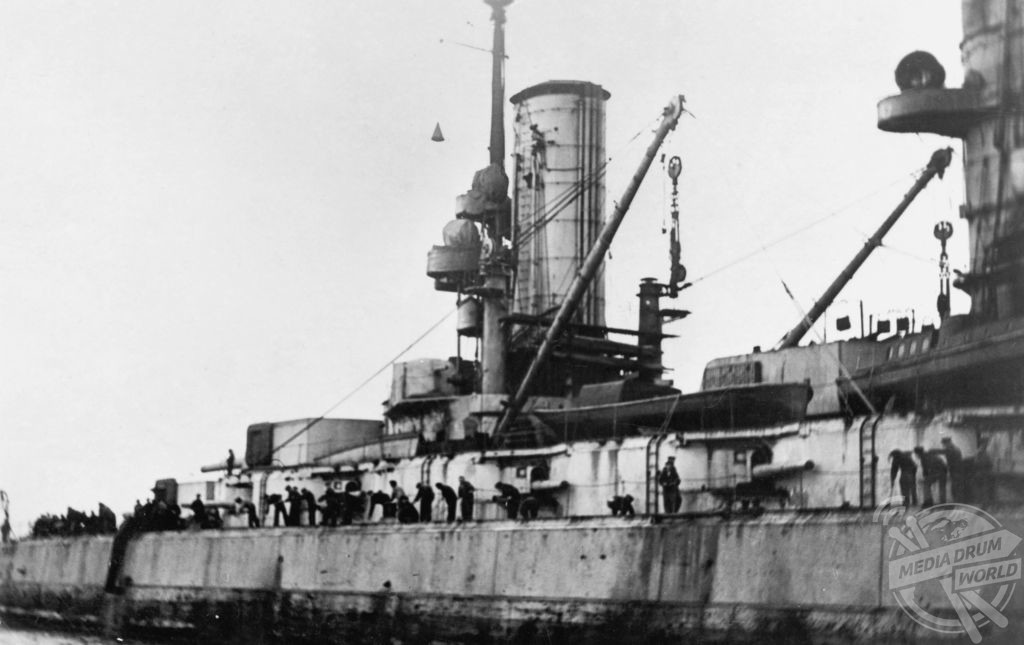

Remarkable photos capture the chaos of that fateful day including a scuttled battlecruiser with only its masts and funnels visible, a boatload of German sailors surrendering after sinking their own ship, and a rare aerial shot which shows the extent of the defeated German nation’s fleet.

The striking shots are included in David Meara’s new book The Great Scuttle: The End of the German High Seas Fleet: Witnessing history – an enthralling account of that momentous Midsummer’s Day, drawing on the eyewitness accounts of those who saw the crisis unfold at first hand. Meara has long been fascinated by the epic maritime phenomenon and even has a personal link to the event.

“In June 2019 we commemorate the centenary of the greatest single loss of shipping in maritime history, an event that made a profound impression on those who witnessed it happen,” he said.

“None of those witnesses are still alive, but many left written and verbal accounts of what they saw, often recording in vivid detail their impressions of the drama and confusion of that day. I have a personal interest in the subject because my mother and uncle were two of the party of Stromness schoolchildren on the deck of the Flying Kestrel, being taken around the German fleet on a sightseeing trip when the scuttling began and the big ships began to turn turtle all around them. My uncle left a detailed account of what he saw, and this gave me the idea of telling the story of that day using as much eyewitness material as I could find. I hope that these on-the-spot accounts, together with a wealth of images, both historic and contemporary, will bring this event alive with vividness and immediacy, as we commemorate the scuttling 100 years after it took place in Scapa Flow.”

When the Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, conditions of the agreement demanded the entire German U-Boat fleet be surrendered and confiscated immediately.

On 19 November the fleet of German warships led by Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter in his flagship, the battleship Friedrich der Grösse, left Germany to rendezvous with Beatty’s ships in the North Sea.

At the rendezvous the ships formed up as required and the joint convoy of 191 Allied and 70 German vessels that sailed into the Firth of Forth, Scotland, on 21 November 1918 was the largest fleet of warships ever assembled.

Four more ships joined them just days later.

Once all the German ships had dropped anchor, British Admiral Sir David Beatty gave the signal that the German flag was to be hauled down at sunset and not to be raised again without permission – even though the ships were still in Germany’s possession. It was a another bitter humiliation for the defeated German sailors.

The 25,000 men onboard the ships were slowly released back to Germany, eventually leaving just a skeleton crew of 1,700 to maintain the ships amid negotiations over the peace settlement. The crew spent four months at sea with little or no entertainment. Fishing and drinking were often the only leisure pursuits available.

As the talks dragged on with little apparent prospect of resolution, von Reuter grew increasingly restless, and feared that his ships would be split amongst the allied forces. On 17 June 1919, he sent a secret letter to his captains that they were “to make immediate preparations for scuttling all ships, to ensure their sinking as soon as possible after the receipt of command”.

When the German government collapsed, von Reuter concluded there was no prospect for a favourable peace agreement and decided to authorise the scuttling. On 21 June he sent the signal. The SMS Friedrich der Grosse was the first to sink at noon; by 5pm, 52 vessels had been scuttled approximately 400,000 tonnes of shipping. The German standard was raised as the boats were sunk. The remaining vessels were beached by a frantic Royal Navy.

Tensions flared as the British tried to prevent the ships from sinking to the sea floor, ultimately leading to the final German casualties of the First World War. Although nobody drowned, nine sailors were shot and killed and sixteen were injured during brawls when they refused to help save the fleet.

In the end, the scuttling served both Germany and Britain admirably. Germany felt it had restored its naval honour and Britain did not have to worry about an allied nation building a navy to rival its own.

Meara’s uncle and mother – Winifred and Leslie Thorpe – offer a child’s perspective of the scuttling, as they were on a schooltrip on a pleasure cruise on the Flying Kestrel at the exact moment von Reuter issued his orders and doomed his fleet.

Thirteen-year-old Leslie recorded the scene as the Kestrel’s crew realised what was happening and made their way back to shore.

“We came alongside with such a bump! We were ordered back to Stromness, and the vessel was then to return to the Victorious. As we came back we saw one ship bottom up, others turning turtle, and a battlecruiser sinking by the stern, turning over, and rapidly going down.”

Meara notes that other children remembered particular details of the scuttling. William Groundwater saw sailors dragging their kit across the deck and throwing it into the boats. Rosetta Groundwater saw men with their hands up, and one man shot and falling overboard. Peggy Gibson retained a vivid picture of the sea boiling as ships turned turtle, great gouts of water and explosions of steam bursting all around, German sailors being swept into the water and clinging to rafts and boats. While some of the children were thrilled by these sights, thinking naively that it had all been laid on for their benefit, others were frightened and anxious, and reduced to tears.

Peggy Gibson recalls: “I remember feeling absolutely amazed that I was there and seeing something that seemed like a display staged for me. I could hardly believe my eyes”.

While Winnie Thorpe, Leslie’s nine-year-old sister, remembers bursting into tears, and her brother putting a protective arm around her. “Never mind, Winnie,” he said. “We are witnessing history.”

According to both children and British naval officers, the scene was one of ‘pandemonium with a strong dash of panic’.

William Caldwell, who lived at Scapa, remembered a man on a bicycle pedalling furiously past his house, shouting something and pointing up the road.

“We followed in his direction up the road until we came to a point overlooking Scapa Flow. There we saw an amazing sight,” he recalled.

“Those fine ships we had seen so recently were now in every possible state of confusion. All were sloping irregularly: some were already half-submerged. They were all listing wildly and even as we looked, one vessel turned over. We saw the gleam of reflected light from her dripping underside as it came up out of the water. Slowly and gently her funnels made one last farewell bow before they plunged beneath the waves. There arose a tremendous column of foam and spray, which at that distance, appeared solid and motionless for many long excited seconds. Then it flattened down and there was nothing. That mighty vessel had gone to the bottom.”

Salvage operations began in 1919 to remove the ships scuttled in the post-war flashpoint, which were a hazard to shipping.

In the years that followed, most of the ships were purchased from the Admiralty to be raised and scrapped by various private companies, the most prolific being Ernest Cox of Cox and Danks Ltd., who purchased 28 ships and a floating dock with which to raise them. He became known as the ‘man who bought a Navy’.

Of the 52 ships scuttled in 1919, seven remain at the bottom of the sea today. They now provide some of the best shipwreck diving in the World.

David Meara’s The Great Scuttle: The End of the German High Seas Fleet: Witnessing history, published by Amberley, is available here.