By Mark McConville

CAN YOU perform this optical trick to view the colourised realities of WW1 with 3D photo-technology developed over 100 years ago?

Michael Harrison / mediadrumimages.com

By unfocusing your eyes and allowing them to drift together to form remarkable 3D images, you should be able to see lifelike officers training in the snow and the Prince of Wales posing at a bench.

Michael Harrison / mediadrumimages.com

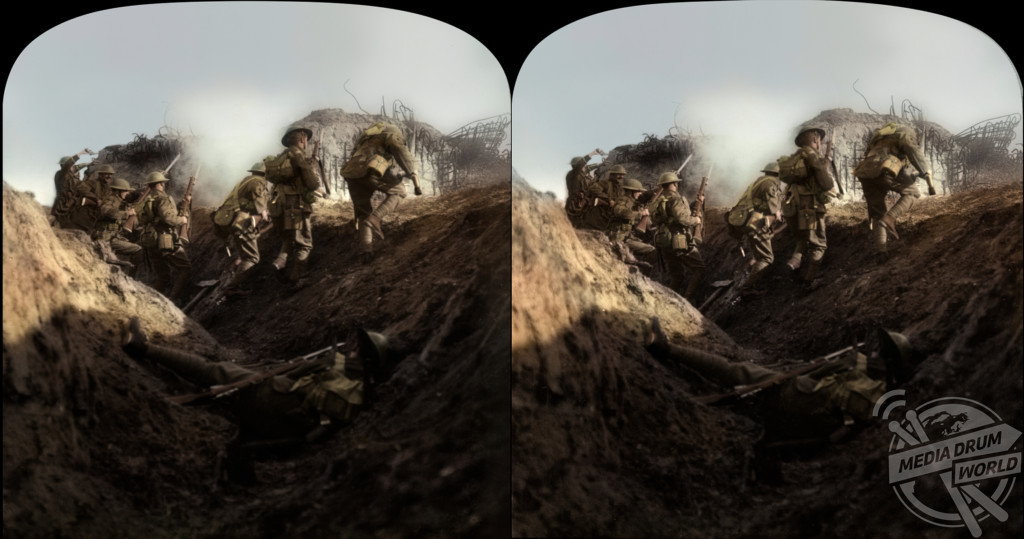

Other incredible stereoviews show soldiers in a trench, an explosion and a regiment waiting for action.

Michael Harrison / mediadrumimages.com

The original stereoviews were colourised by film compositor and visual effects artists Michael Harrison (50), from Bures, Essex, UK.

Michael Harrison / mediadrumimages.com

The stereograph, otherwise known as the stereogram, stereoptican, or stereo view, was the nineteenth-century predecessor of the Polaroid, with an imaginative flair. Placed on cardboard were two almost identical photographs, side by side, to be viewed with a stereoscope.

Michael Harrison / mediadrumimages.com

To view the images in 3D you can cross your eyes while looking at the image on the screen and a third image will appear. By forcing your mind to ignore the two outside images and focusing on the middle image, you will be able to see the 3D of the image. This may take some practice but is well worth the effort. For the best results face the monitor squarely and look straight at the image (not at an angle) and stare at the centre line of the image before crossing your eyes.

“I first got this idea when I rediscovered old black and white stereoviews on eBay a couple of years ago and started to amass a collection,” said Harrison.

“I remembered viewing 3D images in old antique machines at the Sanctuary Wood Trench museum near Ypres in the 80s, and I thought that it would be interesting to see if I could use similar techniques which I have learnt in my job, to try and colourise two slightly different images accurately. It’s been a technical and creative challenge.

“What I see is people and places bought back to life, and made real in both colour and dimension. What I am trying to do is to bring the past into the present.

Michael Harrison / mediadrumimages.com

“I’d like to convey that the people who fought in this war were real people, and not just flat black and white images. Everyone has a history and a family. We should not forget about the past so that we can learn from it, and not repeat the same mistakes.”

Each picture can take Harrison a month or more to do as he fits it in around his day job. He has worked on feature films and television series, including the Harry Potter Films, Dr Who and The Jungle Book.

Working on two images quadruples the length of time it takes to complete each one, according to Harrison. This full collection took the visual effects artist more than a year to do. He explained his process and the problems he ran into along the way.

Michael Harrison / mediadrumimages.com

“After analysing which images work best in depth, I then start by first scanning the images from my collection at a very high resolution,” he said.

“Then I spend time cleaning up/despotting the various artefacts. After that is done, I apply broad brush strokes to get the initial colour tone of the image down, before I start the labour intensive process of accurately layering and colourising in both eyes.

Michael Harrison / mediadrumimages.com

“I refer often to reference images of uniforms and equipment, and also reference my own photographs to see how colours change, depending on the season, weather conditions, and time of day.

“I use a free open source paint programme called Gimp, which is similar to Photoshop. I also use a software called Nuke, which is the main compositing software used on Feature Films and which I have used for over a decade. My place of work has kindly let me use their equipment during evenings, or weekends, as long as it didn’t interfere with the day job.”