By Rebecca Drew

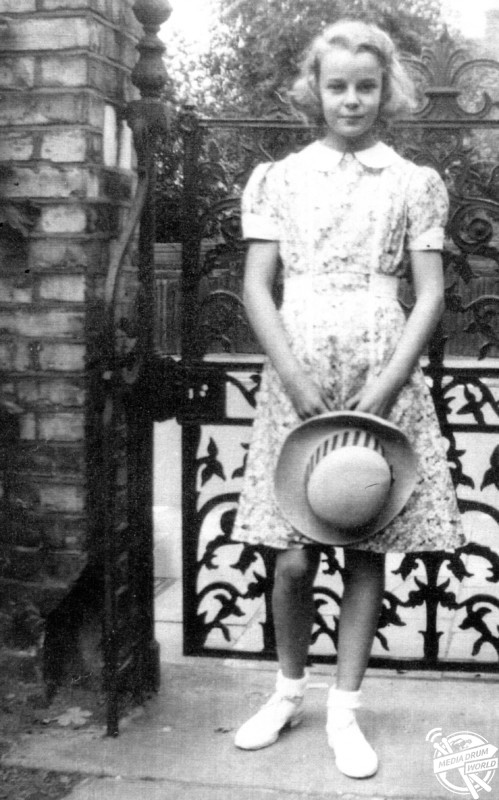

INCREDIBLE black and white images have been released in a new book showing how the lives of children living in Britain were affected during WW2.

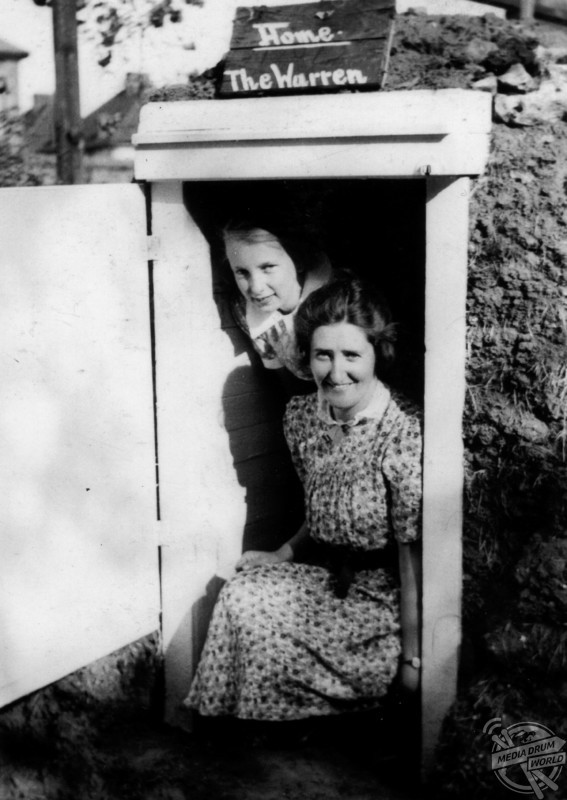

The shocking pictures show children sitting in an Anderson air-raid shelter at the bottom of their garden, a twelve-year-old girl digging a trench for air-raid protection and the remains of a school that was demolished by a German doodlebug overnight.

Other photos show a family playing in their garden in Exeter and in contrast show the ruins of their home after the Blitz in 1942. In another image, a boy is pictured playing war games and a young girl trying on her father’s ARP helmet.

The stunning photographs have been unveiled in the book, Children in the Second World War: Memories from the Home Front by Amanda Herbert-Davies published by Pen & Sword. The book brings together the memories of over two-hundred child survivors of the Blitz.

“This is a sentiment echoed by many who had a wartime childhood, which shows the colossal impact that war had on children. Theirs was a life defined by war.

“On the Home Front, war was everywhere, pervading every aspect of a child’s life, it was in the home in the shape of blacked-out windows, gas-proof rooms, the tin-can air raid shelter at the bottom of the garden.

“It was at school where the rugby pitch was dug up to grow potatoes, when post-raid naps in class were the norm and pupil-spotters kept watch on the school roof for bombs.

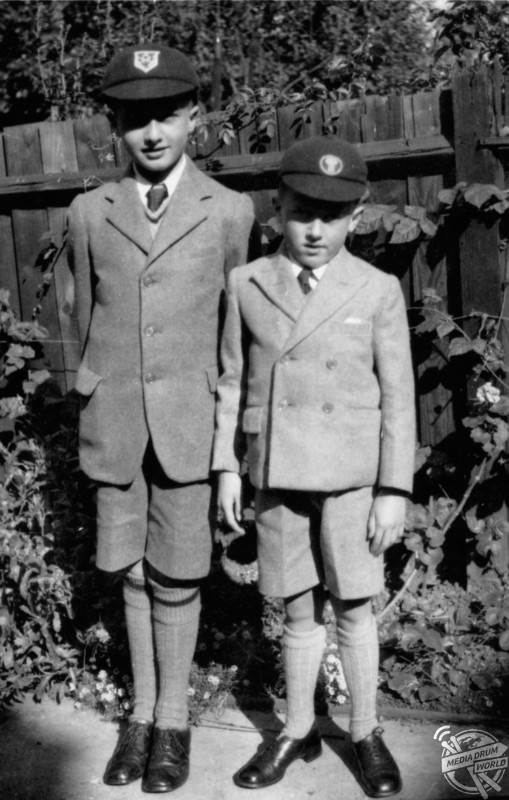

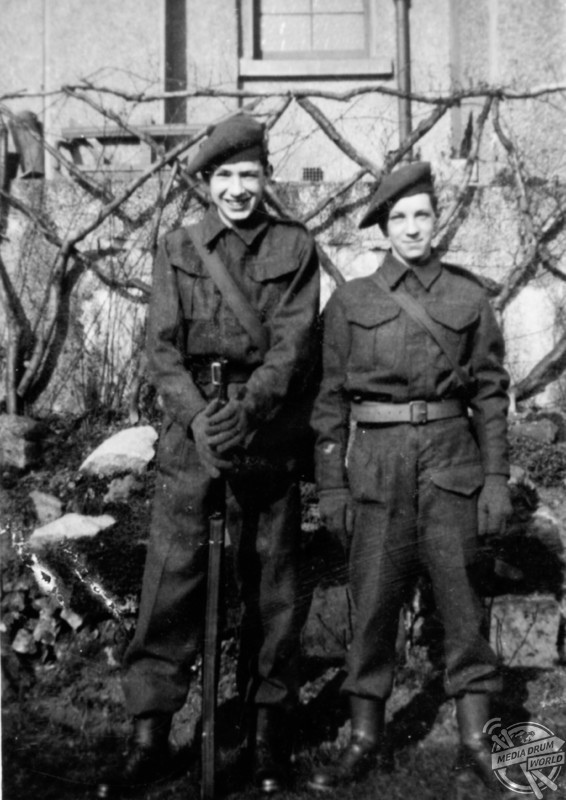

“Even during leisure time, war was at the forefront. Children rampaged through the new adventure playgrounds of bombed-out buildings, paralleling the war with Dad’s home-made Tommy gun, and made illicit explosives in the munitions depot of the backyard shed.

“The war impacted greatly on those children living in urban areas which were a target for bombing.

“These were the children who became the migrants fleeing war, escaping danger for the relative safety of foreign fields – the ‘alien world’ of another county – where their new homes, lifestyles, and even the indecipherable accents, could be very different to what they knew.

“Children in the country did not escape untouched. Off-loaded bombs, watching the sky at night glow from the burning cities, the names of past pupils killed in action read out at school assemblies, all were par for the course.

“For child evacuees in the country, sometimes the longing to come home was harder to cope with than the bombing they had escaped.”

Evacuation of children, mothers with babies and the elderly took place in waves with the first taking place on the September 1, 1939, where over three days, 1.5-million people were evacuated from British towns and cities to the countryside.

By January 1940, half of the number of evacuees had returned home with two further rounds of evacuations occurring in the Summer and Autumn of 1940.

“The biggest impact of the war on many children was undoubtedly evacuation. Many evacuee children faced challenges, coping with feelings of alienation and experiencing prejudice,” explained Amanda.

“Not only did evacuation result in disruption to family life and child trauma but it had a detrimental effect on schooling.

“Some had ‘a good war’, others were left with a lifetime of war-induced trauma, personal tragedy for children was never far away during the war, whether they lived in a heavily bombed city or safely in the country but those who had a ‘good war’ were the fortunate.

“They were free to find the excitement and opportunity in war and have happy memories of childhood. Things that were supposed to inspire fear – soldiers, guns, explosions – were an adventure and part of daily life.

“There is no question that experiencing the war, with or without personal trauma, had a lasting effect on children.”