By Alex Jones

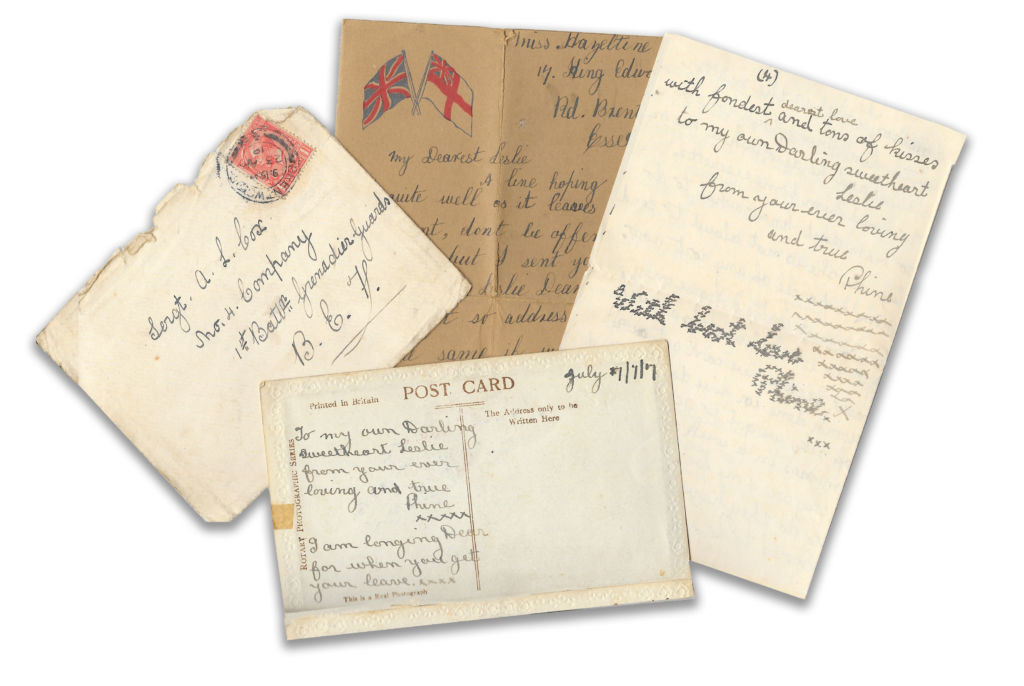

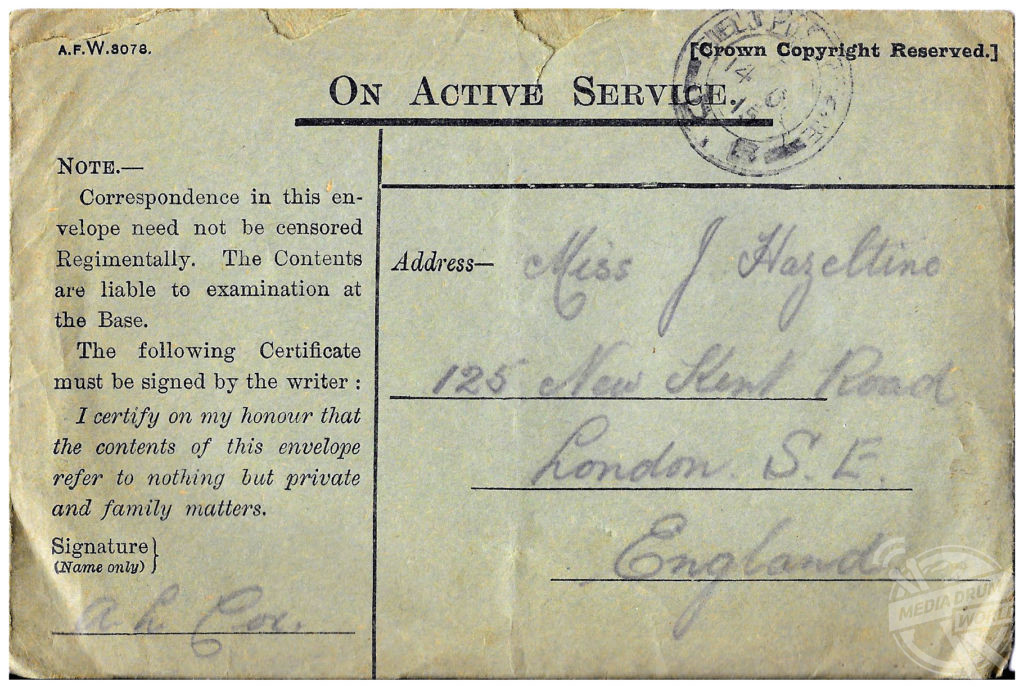

HASTILY scrawled in the aftermath of a brutal battle, spattered with mud from the water-logged French trenches, or signed off with a ‘baker’s dozen’ of kisses – love letters from the frontline of WW1 trace a story of true love between two people, brought together by the army and separated by war months later.

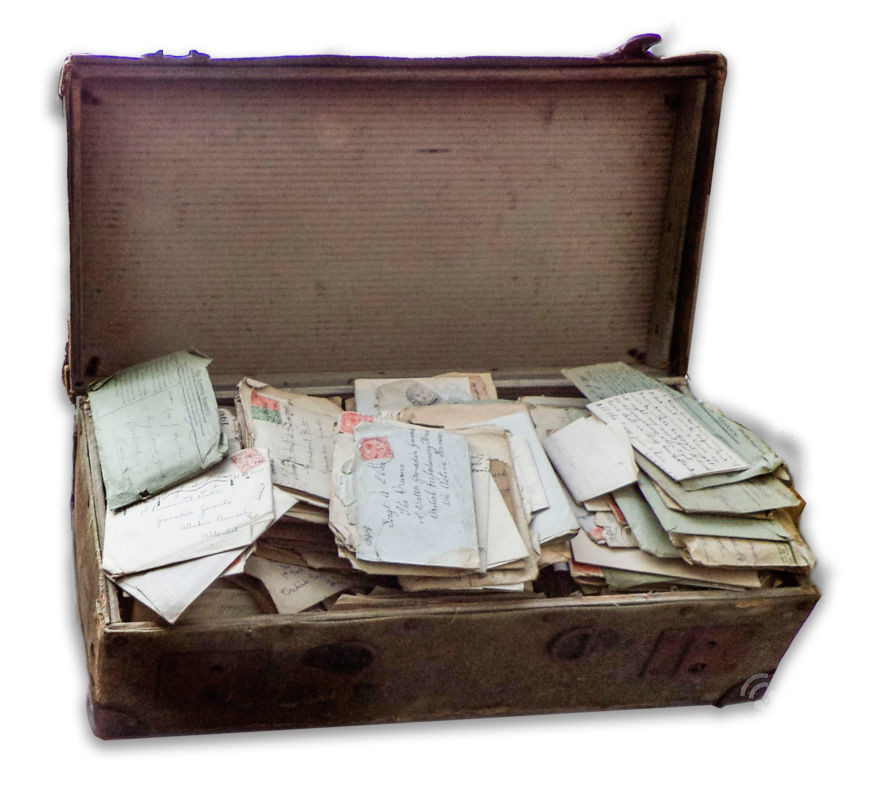

In 2013, writer Stephen Pearmain went up to his loft and found his great-grandmother’s old battered suitcase. Inside were an amazing collection of letters, postcards and photos sent between her and her ‘darling Leslie’ during World War One.

The letters told a remarkable story of love, jealousy, horror, loss, and lustful absence told from two perspectives, at home and on the frontline.

Mary Josephine ‘Phine’ Hazeltine and Albert ‘Leslie’ Cox met at the local barracks in Warley, Essex in the summer of 1914. Phine’s father was a retiring soldier finishing his military career just as Leslie was just starting his. Despite their young ages – they were 14 and 20 respectively – they fell in love in May at a military dance. They started writing love letters to each other. Five months later the young Grenadier was posted to France.

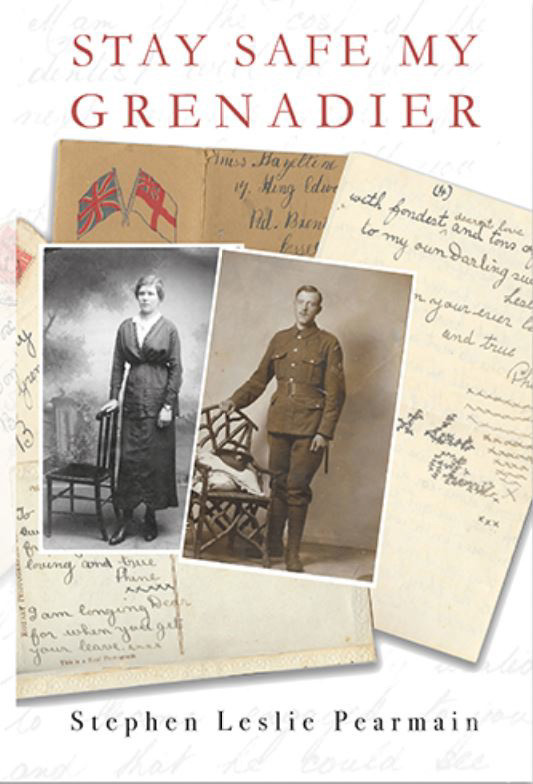

Starting just before the onset of war, Pearmain has compiled these fascinating letters into an enthralling book which captures two ordinary lives during an extraordinary period of history. Stay Safe My Grenadier is a warm-hearted, but frequently brutal, account of Leslie’s war experiences – including some of the Great War’s most horrendous battles – and his harrowing time in the trenches. Back in Blighty, Phine’s messages shines a light on what it was like to live through constant air raids whilst looking after her sick family, building bombs in a nearby munitions factory, and eventually planning a wedding with a partner she was lucky to see once a year.

“This book is about my great-grandparents in World War One,” explains Pearmain.

“It draws from my collection of over 500 letters, including postcards and photos, which my great-grandmother kept in her trusty old suitcase. The letters span over four years of correspondence, from the trenches to the home front, between them both during the war. I decided to write this book as it tells the story of my great-grandparents’ lives, taking part in the Great War and doing their bit for King and country.

“I never met my great-grandparents, but by going through their letters it was like being able to travel back in time and experience what their lives had been like. While piecing together the facts and finding out new things each time, it gave me a real sense of what they were like and I felt that I got to know them.”

As well as the love letters – which includes Leslie’s sweet but faltering proposal and Phine’s equally shy acceptance – Pearmain’s vintage case also included remarkable, never-before-published photos and postcards.

These are the photos the young sweethearts sent to each other as keepsakes during the bloody conflict, to let one another know they were thinking of them. There’s also a photo of their eventual wedding day in September 1918, just weeks before the Great War had ended.

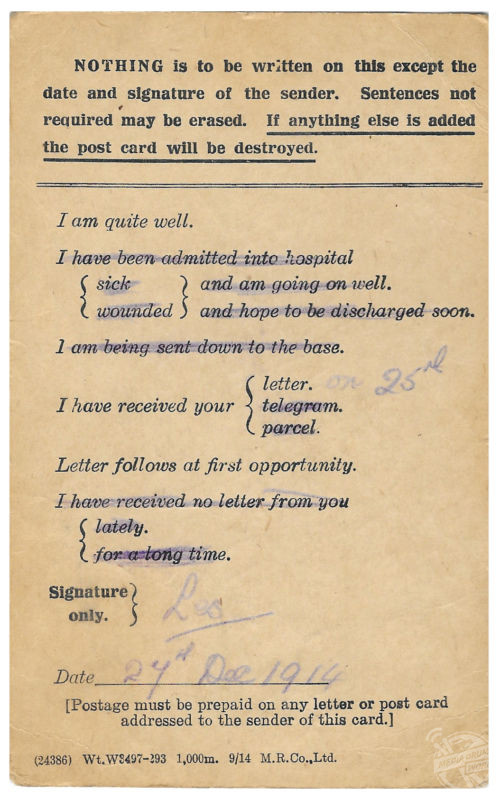

In total, Leslie spent three years and 258 days fighting abroad. His letters were artfully constructed so he didn’t face the wrath of the wartime censors and he somehow maintained a chipper attitude in his letters home to his partner as she constantly fretted over his fate, regularly dreaming ‘something awful had happened to him’.

Occasionally however, the true horror of war would be hinted at in the stoic Grenadier’s writing.

“Just a line to let you know I am quite well, although I have been slightly wounded in the head with a piece of shrapnel shell,” he writes to Phine matter-of-factly.

“I went to hospital but I am out now, and I am doing guards over the German prisoners at the base. I have not heard from you yet because I am not with the Battalion and they cannot send my letters on because they do not know where I am, so do not write again till I tell you. I have not much news to tell you, except that the battle I was in was simply awful, beyond description.

“Well Phine dear I will close now. Hoping your Mam and Dad are quite well and my best wishes to them. With fondest and best love to my dearest Phine, from Leslie. XXXXXXXXXXXXXXX”

In response, Phine states: “For goodness sake try not to go back yet, if you can manage it stay a little while longer, then perhaps the worst will be over, it is too terrible. I am really pleased you are wounded if you were up there you might have been killed so I hope it has happened for the best, I do hope you will get this letter I have sent ever so many but you know it is not my fault.

“I have sent you some cigarettes also but I don’t suppose you will get them now, never mind, so long as you are all right.”

Some of the other topics of discussion are more prosaic, discussing a new clutch of chickens whilst also discussing the deaths of dozens of people in a nearby air raid. Leslie replies by enquiring over Phine’s uncle – who was captured as POW in the early stages of the war – before listing the deaths of numerous friends and comrades.

The dreadful conditions of trench warfare are also described on numerous occasions – although the soldier maintains a stiff upper lip.

“We are still having bad weather, we had a heavy fall of snow yesterday, and it is very cold,” he confesses.

“We have had so much to do lately, hardly a minute to sleep what with digging, sand bagging and bailing water out of the trenches.

“We are still in the same trenches, the same old thing over and over again, nothing of any importance happening. It is becoming rather monotonous, I shall be glad when we make a change, although we are cheerful and happy enough. We are still having a fairly quiet time, the Germans are about 400 yards away from us, but there are not many shots fired during the day, it is mostly artillery duels that do all the damage. Still plenty of mud.

“I do wish the war would end or at least let us make a move. It is so monotonous these long trenches. We dare not move about in daytime, in case we get shelled, we can only work at night so we have a long day of about 16 hours, sleeping and thinking of home and what they are doing there. It is awfully tiring but still it will end someday, and very soon, I hope now.”

Leslie – who was a talented drummer and often served on the front line as such – also had his fair share of lucky escapes.

“I had a narrow escape the other day, I was crossing a field on my own to reach the dressing station, when I stooped down to pick up a piece of an exploded shell, and just as I bobbed down a bullet whistled just over my back,” he writes.

“I thought about keeping the piece of shell as a mascot. But it was too heavy.”

Phine responded: “My word, what a narrow escape you had, what a good job you stooped down, you would have bound to be hit perhaps killed!”

Soon after Leslie again reports: “As you will see by the papers we have had an awful fight in taking the village of Neuve Chapelle, but thank God, I came out of it safely. We were at it four days and four nights and now we are resting, so you can guess how thankful we are for the rest. I had a narrow escape, one bullet went in the back of my right shoulder across my back, and then out under my left shoulder, it cut all my under clothing, but did not even graze my skin. Don’t you think that God was watching over me? I do. Still I am trying to forget that now, and trusting in the lord for the future.

“How is it in Warley? I am always wishing I was still stationed there, I am sure it was the best years soldering I ever did and I suppose this is the worst.”

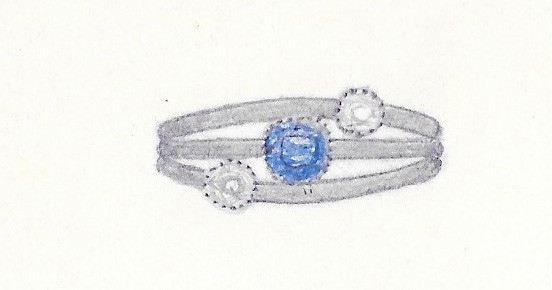

Occasionally the inevitable delays between letters would give rise to jealousy for the young lovers. Phine had sent a letter to her now fiancé – she sent him a cardboard ring-size guide along with one of her letters after he very bashfully asked if she would consider marrying him – worried she had upset him after a period of no correspondence.

Leslie replied: “I felt such a brute when I read your last letter, I know how you feel when you do not have a letter from me. I am so sorry but I am so awfully busy here, and fed up with the place, still I know I am to blame and I feel ashamed of myself for not writing you more often, but I will do so.

“I felt quite hurt when you ask me if I have forgotten you, I think of you a hundred times a day, and simply long for the time when I forget you dear I shall forget everything in this world, and I hope that will be a good long time yet. I wish I could be at home with you dearest, I feel quite sad to hear that you are miserable. Oh roll on this blessed War, so we can all get home again I hope it will not be long now.

“When I read your letter and you said nobody could take my place, I loved you more than ever, if it was possible, because truly speaking sweetheart I am awfully jealous of my girl, and there is nobody in this world could take your place. Ever since the night I first see you at the Cpls first dance I have loved you.”

In July 1917, Leslie took place in one of the most bloody battles of the War, the quagmire of Passchendaele. One of his accounts snuck past the censors after Phine ponders if one of the shells she has produced – as she took up working building shells and mines before the end of the war – was involved in his latest skirmish.

““I have received your letters alright, but have had no time to write before,” he tells Phine.

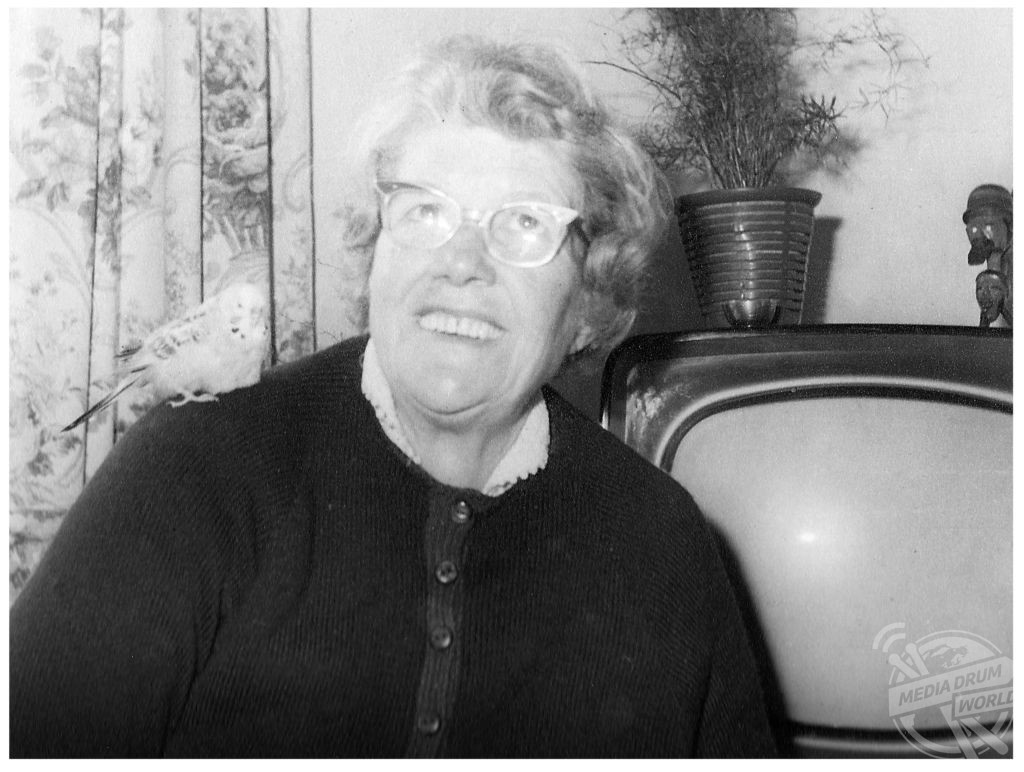

May 1916. As he was at war, Phine had to choose her own engagement ring. In his reply, Leslie wrote: “I am very pleased with the ring, it is very nice, it is uncommon.” Mediadrumimages/StephenPearmain/TricornBooks

“No doubt you know the reason now by the papers, we had a big part in the great push. I am glad to say I have come through alright with the help of God. We had beastly weather and it hampered us a bit, we should have gone much further if it had not rained so. It has not stopped now, when it does no doubt we shall be off again. We are up to our knees in mud and water, owing to the ground being churned up with the shells. There is no doubt we have old Fritz properly beaten now, it will not be long now before the War ends. I am very glad to hear you are doing your bit in the Munitions Factory. I hope you like the work alright. You say it is hard, do not overdo yourself, especially on night work, but from what I remember, you are quite strong enough, at least you used to be with me.”

Phine, still just a teenager, has numerous near misses herself. Especially as her home was directly under bombing run to London and so constantly in the shadow of war.

“Dear Leslie, I thought our last day had come last night,” she writes.

“We had another air raid last night, but they did not get to London, they were beaten back, but we got it instead. They dropped five aerial torpedoes on Shenfield Common and our works shook like anything.

“I had such an awful dream about you again last night, dear.”

At the time his beloved was being bombed, Leslie was out winning a medal for bravery in the field. Unfortunately, why he received the medal has not been recorded. He was typically understated about his achievement with his partner.

“I was very surprised today, I received a letter from one of my old school-masters congratulating me on getting the medal,” one of his letters notes.

“I wondered who on earth the letter was from at first. Anyone would think I had done something wonderful because I have got that blessed old medal. I shall think a lot more of the 1914 bronze star that they are going to give us now. There will not be very many about to wear them.

“It is a bit too rough the way old Fritz carries on. I don’t mind going in the trenches, but I always start worrying when I read that the planes have been over London and Essex. I am always wondering how you are.

“I hope it will not be long before I can go to the dances with you again. The only dance I know now is the “French Crawl”, and I am pretty good at that, keeping well down to dodge old Fritz’s souvenirs.

“No doubt you are wondering how I am, not having wrote you for such a long time, but we are having about the fondest time of our lives just at present, and not a minute to spare to write letters. I have sent a few field cards to let you know I am alright, and I am afraid you must be content with those, dearest, until this big push simmers down a bit.

the letter dated 22nd November 1917. Mediadrumimages/StephenPearmain/TricornBooks

“There is not a bit of truth in that yarn that we have been out cut up terribly. We have had casualties certainly but he has not pushed us back a yard, except where we had to drop back on our own to conform with the remainder of the line, although he has attacked us and tried hard to get through.

“I don’t think I could ever stick another War after this awful lot. Still I don’t suppose there will ever be another like this. Roll on dear when we will not have to put these crosses on paper.”

In June 1918, the war-weary Grenadier was allowed home where he was stationed at Aldershot Barracks in Hampshire. Meanwhile, Phine was still working hard at the munitions factory and looking forward to their wedding day.

Leslie and Phine finally tied the knot on September 21, 1918. They had a wedding reception with relatives and friends and then went on to their honeymoon in Bath, Somerset.

Stephen Pearmain’s Stay Safe My Grenadier, published by Tricorn Books, is available here.