By Alex Jones

INCREDIBLE images capture the ‘second D-day’, the lesser known and controversial invasion of southern France which almost led to Churchill’s resignation.

Operation Dragoon took place in August 1944, just a matter of weeks after the crucial Normandy Landings, and led to the liberation of southern France and wide-scale Nazi retreat. It also almost caused a complete breakdown between the British and American governments and, according to sceptics, saw a high number of casualties and a diversion of troops from more crucial combat regions.

Even after the war, Dragoon was dogged by controversy. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery branded the mission “one of the great strategic mistakes of the war” as the divisive military action left the door wide open for the Soviets to dominate eastern Europe and kickstart the Cold War, a conflict which took the world to the precipice of nuclear war.

was swift and often brutal. This French woman is escorted to an uncertain fate. Mediadrumimages/AnthonyTucker-Jones/PenAndSwordBooks

Breath-taking photos capture the reality of this contentious operation – depicting American troops storming the beaches of the French Riviera, a casualty being rushed for medical attention, and a dead serviceman laying before French troops as they manhandle an anti-tank gun through a liberated French town.

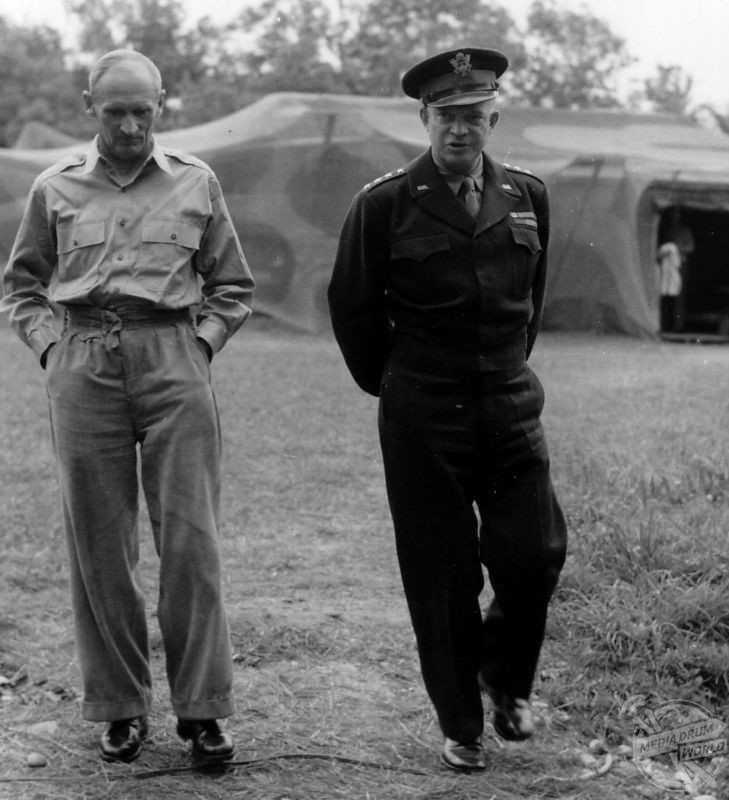

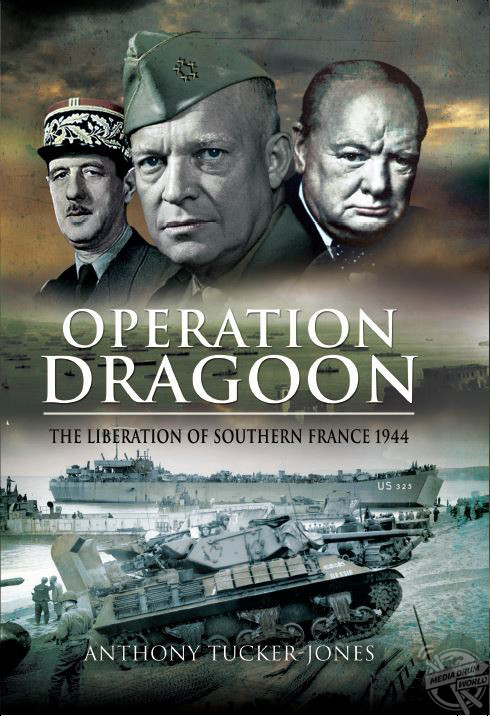

The striking photos are included in Anthony Tucker-Jones’ Operation Dragoon: The Liberation of Southern France, 1944 – an enthralling account of the opinion-splitting campaign, ranging from fiercely heated arguments between Eisenhower, Churchill, de Gaulle and Stalin to the on-the-ground experience of the brave soldiers who fought in this often overlooked campaign.

“To some people, Operation Dragoon – the Allied landings in the south of France – was just a sideshow that needlessly supported the crucial D-Day landings in Normandy, which opened the long-awaited Second Front,” said Tucker-Jones.

“In addition, the resulting diversion of men and equipment hampered the struggling war effort in Italy and Burma, thereby distorting the Allies’ wider strategic effort.

“In reality this other D-Day was of considerable significance, which went far beyond its military contribution to the liberation of France, for the political ramifications were to be far-reaching and helped put at centre stage the leader of the Free French, General Charles de Gaulle.”

Initially the invasion of Southern France was dubbed Anvil, while the invasion of Normandy was codenamed Sledgehammer. The two were planned to be carried out at the same time. In early 1944 however, the plan of conducting two simultaneous landings in France was abandoned due to lack of resources, not least because the landing craft were needed in Normandy. Instead, Operation Dragoon was postponed until August 15th when a large contingent of Free French Forces, together with Americans and Canadians, was to land in an area between the towns of Le Lavandou and Saint Raphael on the Mediterranean coast of France. The Royal Navy, RAF and British commandos also played a small but significant role in the attack.

Though highly supported by Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the operation was bitterly opposed by Winston Churchill. Seeing it as a waste of resources, the cigar-toting statesman favoured renewing the offensive in Italy or landing in the Balkans. Looking ahead to a post-war Europe, Churchill wished to conduct offensives that would slow the progress of the Soviet Red Army while also hurting the German war effort. For exactly that reason, and because a second front would relieve some of the pressure on his own army, Stalin endorsed the plan. To Churchill’s dismay, Stalin was backed by Eisenhower who acceded to the Russian leader’s demand for another fighting front and, correctly as it turned out, believed the ports in the south of France would prove invaluable to supplying the Allied Forces drive into Nazi-occupied regions.

Eisenhower and Churchill had blazing rows over the operation and at one point the British PM threatened to resign, possibly collapsing the UK government. However, his protestations were ultimately in vain.

beachhead. Operation Dragoon was originally supposed to coincide with Overlord. Mediadrumimages/AnthonyTucker-Jones/PenAndSwordBooks

The beaches in France were heavily bombarded for the six weeks prior to the landings. Unlike Normandy, the battle was less bloody as most of the German troops – fully aware of what had happened on Frances’ north coast – defending the landing zones were more willing to retreat or surrender. The French Resistance also had a big impact. It was still a costly campaign however. In conducting Operation Dragoon, the Allies sustained around 17,000 killed and wounded while inflicting losses numbering approximately 7,000 killed, 10,000 wounded, and 130,000 captured on the rapidly retreating Germans.

According to Tucker-Jones, the operation itself was seamless if not ultimately pointless.

“Despite de Gaulle’s and his generals’ demands for French pre-eminence, experience dictated that American forces should conduct the initial assault in the south of France with the French Army following up in the second wave,” the author explained.

“In the event, the invasion was conducted in an exemplary fashion in the face of minimal resistance; the liberation of the major cities of Marseilles and Toulon was achieved way ahead of schedule; and Hitler’s Army Group G was put to rapid flight. The situation seemed highly promising.

‘fortress’ city yielded 17,000 German prisoners. A dead soldier lays at their feet. Mediadrumimages/AnthonyTucker-Jones/PenAndSwordBooks

“However, subsequently there were bitter battles with the tough German rearguard as it sought to hold France’s southern cities and cover the withdrawal.

“Pushing past the mountains that border south-eastern France, the invasion force found itself held up at the strategically crucial Belfort Gap, the gateway to Germany, until the end of the year.

“In the meantime de Gaulle was left in control of Paris and much of France, and the Allies never did break free from Italy before the war ended, leaving Stalin a free hand in eastern Europe and the Balkans.

“Churchill had been right all along, although Eisenhower, great statesman that he was, ultimately had the good grace to admit that he had been wrong. This, though, never made up for the fact that Dragoon should never have taken place.

“However you look at it, in strategic terms Dragoon was a nugatory exercise. It was not conducted in parallel with Overlord owing to shortages of amphibious transport, thereby losing its diversionary impact. In addition, the success of Overlord meant Army Group G would have been forced to withdraw from southern France anyway to avoid being cut off, regardless of an invasion in the south. The timing of Dragoon meant it did not take any pressure off the Allies fighting in Normandy, since the Nazi’s better units, especially their panzer divisions, had already been drawn north by 15 August.”

In the interests of balance, Tucker-Jones does concede there were positive aspects to Dragoon as well.

“To the Americans’ credit, General Patch’s US 7th Army and de Lattre’s French 1st Army cleared south and central France in half the time expected, taking some 100,000 prisoners at the cost of about 13,000 casualties as of mid-September,” he added.

“Likewise, from the supporting logistical supply standpoint Dragoon was a triumph. Despite German efforts to wreck the facilities at Marseilles and Toulon, both ports were open for business by 20 September 1944. By the end of the month over 300,000 Allied troops, 69,000 vehicles and nearly 18,000 badly needed tons of gasoline had poured into France via the Dragoon bridgehead. Ultimately some good had come of it. Churchill, though, always felt that a much bigger opportunity had been lost and the world became a much worse place for it.”

Anthony Tucker-Jones’ Operation Dragoon: The Liberation of Southern France, 1944, published by Pen And Sword Books, is available here.