By Rebecca Drew

FASCINATING photographs showing the British response to soldiers’ facial injuries during WW1 have been released in a new book charting the early development of facial plastic surgery.

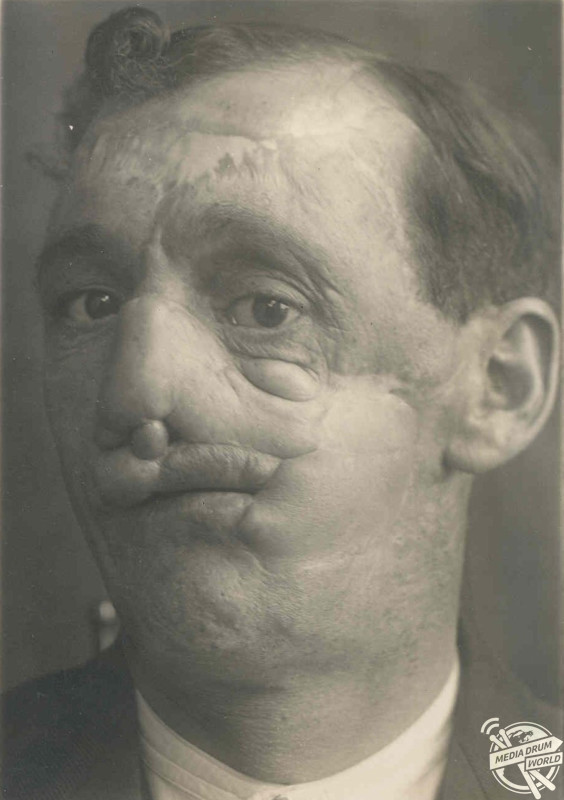

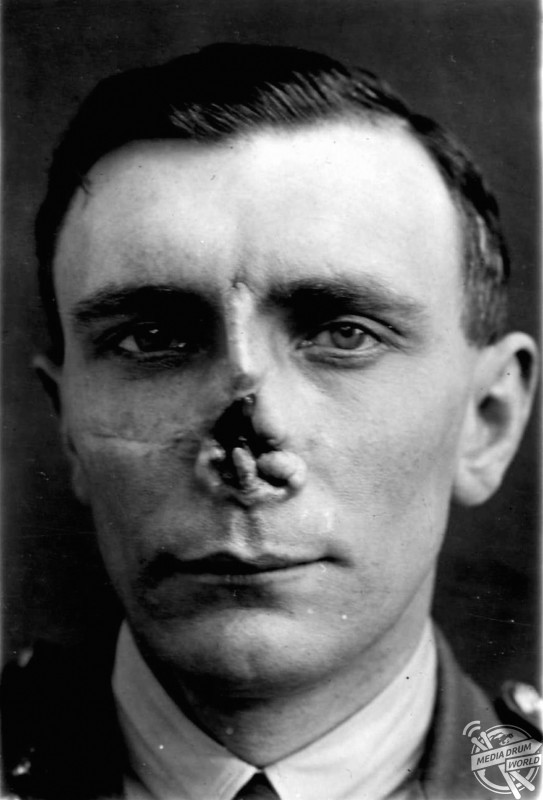

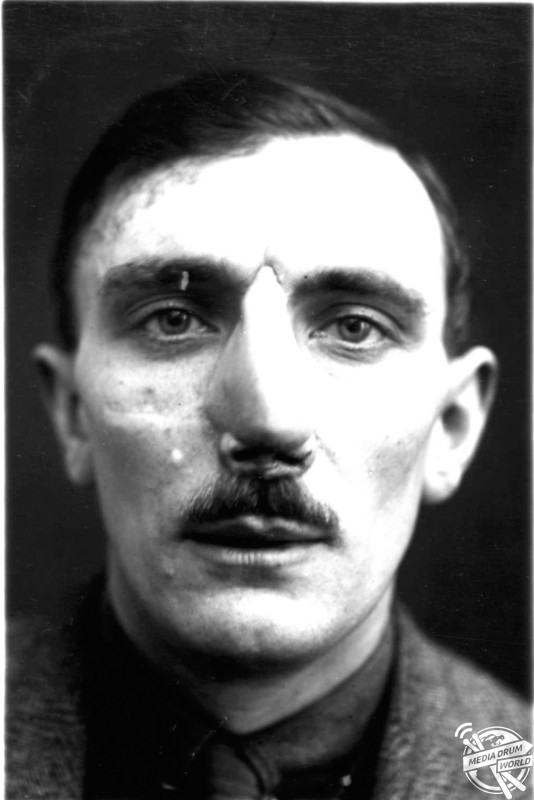

The incredible black and white images follow the work of young surgeon Harold Gillies, who transformed the faces of those who were injured and shipped back to Britain after fighting on the front lines. One set of before and after pictures show Private William Thomas from the 1st Cheshire Regiment who was admitted to The Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup, East London with the centre of his face missing in November 1918 and six years later, after 19 operations which included a cheek, upper lip and nose reconstruction.

Other breath-taking images show Arthur Mears, who was treated at Sidcup after losing his lower jaw in September 1917 and had this reconstructed using the rib, Gillies sitting inside the plastic theatre of The Queen’s hospital; and The Royal Army Medical Corps loading British and French wounded onto a hospital train at Doullens, France, in April 1918.

The photos have been released in, Faces from the Front: Harold Gillies, The Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup and the Origins of Modern Plastic Surgery by Andrew Bamji and published by Helion & Company.

“During the Great War, facial injury became a major focus of medical attention for the first time,” said Mr Bamji in the book’s introduction.

“Of all the horrific injuries suffered by soldiers during the conflict, facial wounds were the most obvious and had the capacity to cause the most reaction among those who viewed the wounded.

“This book is about the men who suffered from facial wounds, and the surgeons who repaired them.

“This work places emphasis on one man, Harold Gillies, whose drive and innovative approach were fundamental to these developments.”

In January 1916, Gillies established a dedicated ward for patients with facial injuries at the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot, Hampshire.

After the Battle of the Somme, steps were taken to set up a new hospital specialising in the treatment of patients with facial injuries at Sidcup, South East London. The Queen’s hospital opened in August 1917 and treated more than 5,000 patients up until the mid-1920s.

“Studies of the First World War often focus on the events and the fatalities of the war, or on cultural memory of the conflict,” he added.

“Historians, writers, artists and poet speak of heroic sacrifice.

“However, few of them give thought to those whose lives were not ended by the conflict, but were changed forever.

“This book talks of those who were left to grow old, and whom age did weary, and is dedicated to their memory.”

Published by Helion & Company, Faces from the Front: Harold Gillies, The Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup and the Origins of Modern Plastic Surgery by Andrew Bamji is now available to buy on Amazon for RRP £29.95.

For more information see www.amazon.co.uk/Faces-Front-Gillies-Hospital-Origins/dp/1911512668/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1506345212&sr=8-1&keywords=faces+from+the+front