By Alex Jones

A BRUTALLY honest account by a WWII prisoner of war describes the gut-wrenching treatment British soldiers received in German camps, bringing joy in abysmal conditions to thousands of POWs through music, and the crippling realisation that hundreds of thousands of Jews were being callously murdered just a short distance from his camp.

In April 1940 Drum Major Henry Barnes Jackson, nicknamed ‘Drummie’, stepped off a ship at Le Havre, France – the same port he was docked at some 25 years earlier when he ran away from home to fight for Britain in the Great War, despite being underage, and spent three years striving to survive in the dank, muddy trenches that became his home.

Now a father of four and proud husband at the ‘ripe old age’ of 40, Jackson was once again donning a uniform and preparing to fight for his country against the Germans. Carrying his music case with him – as he was a talented band leader and practiced musician on any number of instruments – and his beloved war diary, Jackson was set to spend the war offering medical assistance to injured soldiers.

However, his story would prove to be very different. Jackson would see out most of the Second World War in various prison camps across Poland, entertaining troops and Nazis with his musical talents.

After a brutal introduction to the war Jackson was captured as he tried to evacuate an ambulance full of injured men to Dunkirk as a wave of Nazi aggression saw Allied Forces pinned back against France’s northern coastline. His van took a wrong turn and he was ambushed by German soldiers.

Recalling that hellish day in his war diary, Jackson wrote: “We are ordered to dismount and a Jerry officer points to me and beckons me to him.”

“He tells me to take off my gun belt and throw away my revolver. He smashes me in the face with the butt of his rifle, and my head ricochets in response to the loud crack, blood oozing from my nose. He takes two steps towards me and slaps my cheek and then, in broken English, he jeers, ‘a long way from Tipperary, a long way now, hey?’

“His eyes flash at my lack of response and he continues to hit me, his face twisted with hate and loathing, spittle flying from his ugly mouth. Then he orders me to stand against a wall. This is it. I feel my time is up. The Jerry officer bends down and picks up my revolver. He hands his rifle to a grinning bastard behind him. I watch on as he raises my own gun to my head. I’ve been in critical situations many times in my life, but I never felt that I was about to face my Maker.

“My eyes well up with tears of deep regret as I pray that I will live to tell my dear sweet wife how deeply I love her but, as I stare down the barrel of my own gun, I doubt my prayers are going to be answered.”

Miraculously, the Nazi officer pointing the gun at Jackson is distracted at the very last second by the gold watch glinting in the Drum Major’s pocket. He hands it over and goes to tend his men, constantly fearing a bullet from behind, which fortunately never arrives. Jackson spends the evening helping the desperately injured soldiers and trying not to think too much about the fact he was now a prisoner of war.

and Reveille. Mediadrumimages/HenryBarnesJackson/JaciByrne

“We are ordered to fall in, and we start what is called by us prisoners, for obvious reasons, as The Nightmare March,” states Jackson’s diary entry, the day after his capture.

“There are many horrific incidents that happen on this march that I will leave out of these memoirs but, on my life, I swear they will never be forgotten—and never ever forgiven.

“When the sun comes out it gets hot and we’re all parched. The French townsfolk, bless them, place buckets of water on the side of the road, and it’s a scramble to get a drink before the merciless guards come along and kick the buckets over out of sheer spite. They wish us dead. It makes it easier on them.

“The Jerry guards are absolute bastards. They find it amusing to stop us British prisoners while they allow the French to get far ahead before making us run to catch up to the Frogs. Naturally, many poor chaps are hardly able to walk, never mind run, and they have to drop out. On hearing shots, we know only too well what has become of them, each gunshot reverberating through our bodies as we trudge onwards, thoughts of our fallen comrades a terrible burden to bear.”

After miles of tramping with no food, little water, and the demoralising loss of friends and colleagues to German gunfire. The Drum Major eventually ends up on a crowded, disease-ridden train and to Camp Schubin in Poland.

“I cannot describe the horror,” he wrote.

“The stench of wasting bodies. I feel as if I’m one of the walking dead, but I manage to make it to the camp, which I’m told is to be my home for a good while. We’re informed there are no barracks available to us. No tents, no blankets.

“The conditions here are shocking and the food indescribably awful and meagre at that. It is hard to keep going, and many don’t, succumbing to dysentery, which is a horribly painful and degrading condition to suffer. We are all in a filthy condition. The heat is unbearable, made more so by the reek of human wastage. Men are beginning to die like flies all around me. I imagine this is not only due to physical exhaustion as a result of the arduous journey here and starvation and disease, but from the sheer mental anguish caused by Jerry’s cruelty, which is beginning to increase daily.

Blechammer 1943. Mediadrumimages/HenryBarnesJackson/JaciByrne

“I find myself attending more and more funerals, often as a coffin bearer. Today it is of a chap who was brought in dead from a working party. The Jerry guards say he died from pneumonia but, as I march alongside the makeshift coffin, blood is running from it and dripping in gory, gelatinous globules onto my boots. I feel my chest rapidly rising and deflating with anger, and I strangle a scream of injustice, knowing that if I start to protest, I will be shot.”

Throughout the horrors unfolding before the Drum Major’s eyes, music is his one solace and he does all he can to cheer himself and the men around him, many of whom feel completely bereft of hope.

“I’m glad to have been blessed with this God-given talent for music; to be able to entertain the lads and see the joy and hope in their eyes; eyes that may well soon be filled with nothing but terror before they become filled with nothing but lifelessness,” he observed.

“I keep reminding myself that if I can survive this, I can survive anything, and I want to take that attitude back to England with me and hand it on to my girls. Music is my saving grace and, although I can’t play due to having no musical instruments, I do spend a lot of time thinking about, singing and composing music. For me, where there is music, there is hope.

“You should have seen spirits in the camp soar when our company receives some musical instruments and music sheets from the Red Cross.”

1943. The Britis referred to Auschwitz as Heaven Camp as nobody left it alive. Mediadrumimages/HenryBarnesJackson/JaciByrne

Jackson spent the next few months organising concert parties and stage shows to great acclaim. To his disgust, he was often made to play for his captor’s pleasure.

A passage in his war diary reads: “Some of the lads dress up as ‘girls’ for chorus work and I have never seen better female impersonators anywhere. Some of the pieces we play are: ‘Light Cavalry’, ‘Florentiner March’, ‘Ave Maria’ and ‘Wine, Women and Song’. The Jerries, seated in the front rows of the concerts, beam with delight at being entertained, but it’s the faces of our boys that we concentrate on and we bow to them on their applause.”

These flickers of light relief were in stark contrast to the prison’s gruelling day-to-day routine however.

Jackson is often called upon to attend funerals, many of the prisoners have taken their own life, where he uses his musical talents to play The Last Post. Conditions in the camp are worse than ever.

“We hear that they decided last month that [the Nazis] need to completely eradicate the Jews,” scrawls the horrified author in his war diary which the prisoner of war religiously kept hidden from the thuggish Nazi guards.

“I cannot conceive of how they can have such hatred for the Jews, nor how they ever imagine they can simply erase an entire race of people. Rumours are still rife regarding the treatment of the Jews, some of them truly disturbing, and I also hear more and more horrors regarding stocking experiments being done on the poor beggars in the name of science.”

Unbelievably, things only get worse for Jackson and his fellow inmates in 1944 as they’re moved to a labour camp in an area called Blechhammer, which is a sub-camp of Auschwitz or ‘heaven camp’ as the Brits call it.

“We pass a civilian concentration camp, and all the prisoners are terribly emaciated and have their heads shaved. It is a pitiful sight indeed,” Jackson states.

“Their lives are worth absolutely nothing—the Jews—less than the rats that infest the camp. It is now pretty common knowledge that the Jews are being killed en masse. We have named that camp ‘Heaven Camp’ because no one leaves it alive. The Jews are absolutely terrified of being taken there for obvious reasons. A train goes right through the camp. Any Jew too sick for work, too frail, too old or too young is packed off there. When the Jews arrive, it is believed they are given a towel, told to strip off, and are told they are going for a bath, but there are rumours that it proves to be a lethal chamber. This mass killing is simply unthinkable to us.”

Fearing for their lives, people start to contemplate escape, knowing they take their life in their own hands by doing so. Jackson, who has by now earned the nickname Kapellmeister (The Music Maker) in camp, helps in whatever way he can.

“One of my violinists escaped along with two other men a fortnight ago,” states the POW’s diary on 29 May 1943.

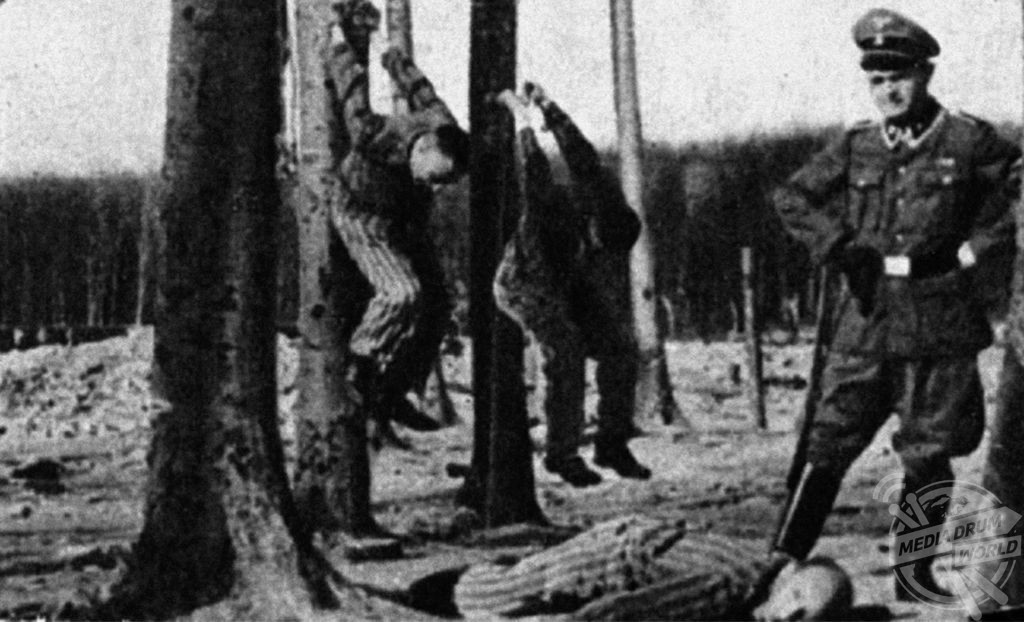

taken at Buchenwald. It appears the victims are Jews. Mediadrumimages/HenryBarnesJackson/JaciByrne

“The two other men were captured the next day, but my violinist is still at large. The evening he escaped my orchestra was to give a concert in the next camp, so, to cover his getaway, I had to take another chap along to the concert to play the escapee’s violin. We had arranged all this previously and were very well organised, although my violinist’s replacement was not a particularly good player, but the rest of the orchestra just drowned him out, and Jerry didn’t seem to notice. It was wonderful to know that we were outsmarting Jerry, if only in a small way, and I think the orchestra played better than I have ever heard them play! Anyway, my violinist got a good head start, and our lads have spent hours talking of him and sending their prayers.”

Unfortunately, the violinist was found and returned to camp a few weeks later in “a terrible way”. His eventual fate is unknown.

Despite the constant barbarity, lack of basic human dignity and four years in containment. Jackson eventually hears the good news in June 1944 that the Allies have successfully invaded France and that the tide of war is turning.

Months later – after yet another lethal march in the cold and snow to evade the encroaching Russian army and a posting to yet another awful POW camp – Jackson ends up in an Austrian barn, on the cusp of death. He has witnessed the deaths of hundreds of men in recent weeks as the chaos of the war in Europe’s final chapter wreaks havoc across the continent. Just moments before he feels he would draw his last breath, Jackson is found by an Australian soldier who tends to him.

After being tended to for his injuries and malnourishment, Jackson was able to return home to Whitehaven, Cumbria to the warm embrace of his family. Dazed but deliriously happy with his own freedom, Jackson still felt a sense of burning outrage over the inhuman treatment he witnesses in the Nazi camps.

“At the end of May 1945, we heard that Heinrich Himmler [a mister who helped orchestrate ‘The Final Solution’ and the death of 6 millions Jews] had committed suicide via a cyanide capsule. This incensed us all, as we recalled his many monstrous actions during the war, particularly towards the Jews. We were only now beginning to learn of the truly sadistic treatment of the Jews who were so savagely targeted by a crazed leader and his elite group of madmen. With so many others in the upper echelon of the Nazi Party dead by their own hands, we had all been looking forward to Heinrich Himmler having his day in court—and what a day that would have been. Not to mention how he would have been made to suffer in prison. But Himmler had taken the coward’s way out. My heart wept for humanity.”

Dazed from the series of events that saw him rescued from almost certain death in Austria to ending up back in ‘Blighty’, Jackson struggled to make sense of what had happened to him over the five years he spent under Nazi lock and key.

“The officers who repatriated us had advised us not to discuss our war experiences with our loved ones,” he starkly notes in one of the diary’s final entries.

“They said that we couldn’t possibly expect anyone who hadn’t personally gone through such indescribable horrors to identify with them. They told us to forget the war—to place it into a padlocked box and shove it in the very back of our minds. Said we should forget what we’d witnessed—the horrors, the losses of our mates, the mental strain, the deprivation and the torture. Well, that was all very well for them to say, but how did one ever get over such a thing? How did one simply forget?

“Oh, I wanted to. I really wanted to and, like most of the chaps, I had vowed to never again talk about the war.

“But I’m afraid there are reminders all around me.”

Drum Major Henry Barnes Jackson’s story is told in The Music Maker, a compilation of his war diary edited by his granddaughter Jaci Byrne and published by Pen And Sword Books. Available to order here.