By Alyce Collins

THIS STUDENT scientist who was told she was ‘FAKING’ her disability when she got out of her wheelchair admits she feels nervous asking someone to give up their priority seating on the bus because of DISCRIMINATION but hopes to diminish the stigma around invisible illnesses and one day find a CURE.

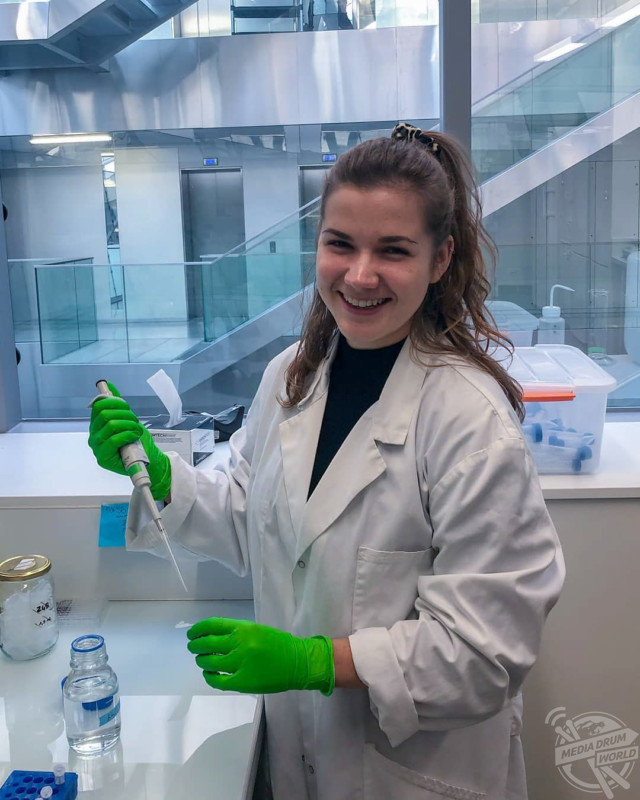

Graduate student, Sara Whitestone (24) from Ohio, USA, who is currently studying in Bordeaux, France, developed POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome) in 2010 yet the condition had been undiscovered in her for two years.

Sara had never heard of POTS before but when her symptoms developed, she went from being able to run a half marathon to suddenly being unable to walk between her bedroom and bathroom without fainting.

While studying her undergraduate degree in neuroscience at the University of Cincinnati, Sara’s POTS diagnosis played havoc with her studies, preventing her from attending classes.

In 2012, Sara began using a wheelchair to get around campus more in order to prevent POTS from hindering her day-to-day life. It took years for doctors to diagnose Sara because she wasn’t believed for a long while, but she admits that when people see her in a wheelchair, they assume she must be paralysed. Although, people who have seen Sara get up from her wheelchair have also accused her of ‘faking’ her illness.

Disability discrimination is something that Sara hopes will lessen over time as people become more accepting of illnesses you can’t see straight away. Assuming that Sara is healthy at face value can work both positively and negatively as she admits that it can help her in job interviews, yet she feels nervous to ask someone to give up their priority seat on the bus.

Being diagnosed with POTS spurred Sara on to further her career in neuroscience as she hopes to continue researching and one day find a cure for the debilitating condition.

“I was sick for two years before I was diagnosed, which is a relatively short time compared to other cases,” said Sara.

“I had a viral onset and no obvious symptoms before. It happened seemingly overnight. I ran my first half-marathon just a few months before I got sick.

“Symptoms came on very suddenly and I went from being an active long-distance runner to not being able to walk from my bedroom to the bathroom without passing out.

“Now, most of the time I’m fully mobile, but when I’m experiencing severe flares or moving between medications or doses, I’m more likely to need mobility support

“Sometimes I’m too sick to function yet other times I can cycle, work and travel. Sometimes I will have bruises on my face from smacking my head passing out, yet people tell me that I ‘don’t look sick’. But I am sick, every day.

“If I had a coin for every time someone told me I ‘don’t look sick’, I could have personally funded an entirely new research and education centre by now – probably even started to pay off my student loans.

“Disability discrimination is rampant in both obvious and subtle ways. When I used a wheelchair, people were aware that I was disabled but assumed I was paralysed. Then, when I finally gained the strength to stand up out of my wheelchair, people accused me of faking it.

“I can ‘pass’ as non-disabled, which might work to my benefit in our ableist society, such as in job interviews, but then it can create even more obstacles when asking for a seat on the bus. It’s something I struggle with constantly.

“Once, I had a specialist rush me out of his office because he refused to believe I could be sick or have tachycardia ‘so young’, and he wouldn’t check my heart rate, which was unreasonably high.

“Doctors are only humans who practice medicine based on research. Modern research is only just now beginning to pay attention to these invisible illnesses thanks to patient advocacy.

“Medical practitioners are extremely burdened by the stress of their work, however I’m not alone in having negative experiences with doctors. It’s very important to be your own advocate and now I have a handful of amazing specialists who have saved my life.”

When using a wheelchair first became a reality for Sara, she pioneered to make the University of Cincinnati campus more accessible. Now, Sara has set her hopes on making medical advances by studying disorders of the central nervous system and one day find a cure to improve hers and other people’s lives.

“Before we can even dream of a cure, I believe it’s our responsibility to take care of those currently living with these devastating illnesses,” said Sara.

“So many people don’t have access to adequate healthcare, treatments, financial support, or belief from their doctors and families. I hope that someday I will be able to contribute directly to the research to develop new pharmaceutical tools to diagnose or offer some relief for these symptoms.

“Many times, you hear stories of people overcoming their disability in the media. But my disability isn’t something that I feel I have overcome to be able to be a neuroscientist. It’s important to uplift the voices of disabled folks without falling into the traps of preaching.

“I live with the symptoms of this illness every day. The relief I have found, or this improved quality of life, comes from my ability to seek and receive adequate medical care. However, this is still no cure.

“This disease may affect some people more severely than others, and I am grateful that I have the ability to pursue research. I am motivated every day to work on closing this gap between the research bench and the patient bedside.”

To see more, visit www.instagram.com/saramckw or www.bisousfrombordeaux.com