By Alex jones

EIGHTY years ago, parents across the UK were forced to make a gut-wrenching decision – risk your child’s life by keeping them with you in the city or send them to live with strangers on the other side of the country.

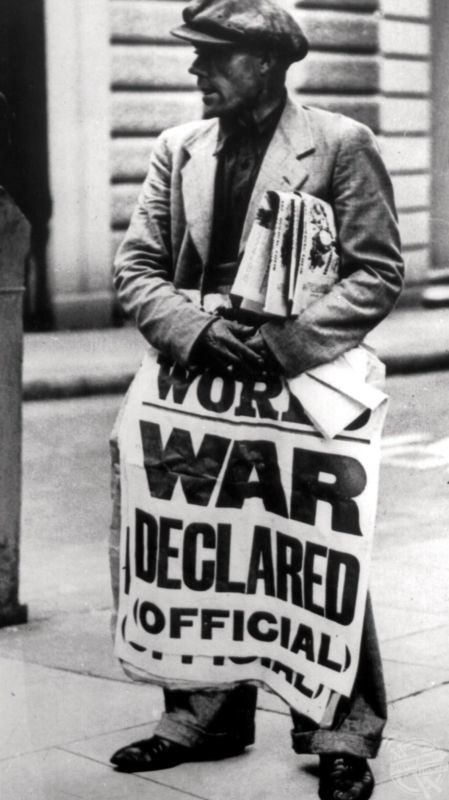

In the late summer of 1939, another world war was looking increasingly imminent. Knowing that scientific advancements made throughout the Great War and beyond, the UK government and its citizens knew that air raids would be frequent, brutal, and deadly. The order was made to evacuate all school age children from densely populated towns and cities – including London, Birmingham and Glasgow.

Heart-breaking monochrome images from 1939 capture sobbing parents wishing their children farewell, knowing that they were to be transported hundreds of miles away and barely contactable; a crowd of schoolchildren – some smiling, some more pensive – preparing for their grand adventure; and a young helper assisting an apprehensive little boy with his luggage tags.

Evacuation took place in several waves. The first came on 1 September 1939 – the day Germany invaded Poland and two days before the British declaration of war. Over the course of three days 1.5 million evacuees were sent to rural locations considered to be safe.

The country was split into three types of areas: Evacuation, Neutral and Reception, with the first Evacuation areas including places like Greater London, Birmingham and Glasgow, and Reception areas being rural such as Kent, East Anglia and Wales. Neutral areas were places that would neither send nor receive evacuees.

It was a huge logistical undertaking. The process involved teachers, local authority officials, railway staff and 17,000 members of the Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS), who provided practical assistance and cared for the exhausted, often tearful, evacuees.

Parents were issued with a list detailing what their children should take with them when evacuated. These items included a gas mask in case of a chemical attack, a change of underclothes, night clothes, plimsolls (or slippers), spare stockings or socks, toothbrush, comb, towel, soap, face cloth, handkerchiefs and a warm coat.

Throughout the war, over 2.5 million children – and countless foster families – were forced to cope with the realities of evacuation and the feelings of abandonment, confusion, and separation that came with it. By the close of the war, many of the evacuees had known their adopted families for longer than they had their real ones. For those who had become accustomed to a rural life – or had resented every moment of it – it was a tremendous shock to return to the comb-battered streets of their home town and their vanished childhoods.

However, without the evacuation protocol – jauntily named ‘Operation Pied Piper’ – the civilian death toll in the UK would have undoubtedly been far higher, and the average age of the dead dramatically younger.