By Alex Jones

GRAPHIC pictures snapped of atrocious war crimes by US soldiers and demoralising snapshots depicting the grim reality of the Vietnam War provoked the end of the conflict – according to the tormented US forces photographers that captured them.

Distressing photos from the infamous war, which directly involved American troops between 1964 and 1973, and include a group of utterly terrified Vietnamese men, women, and children just seconds before they were mown down by US soldiers; An elderly local woman picking through the remains of her home, razed to the ground by fighting; and three US troopers clearing a ‘cave’ of Viet Cong fighters moments before they were injured by a grenade after an initial ‘surrender’.

The gruesome shots are included in Dan Brookes & Bob Hillerby’s new book Shooting Vietnam: Reflections on the War by Its Military Photographers, a frequently disturbing collection of first-hand accounts written by military combat photographers and photo lab personnel (“lab rats”) who documented the war and the country, on and off the battlefields.

“Vietnam was the most photographed war in history and will probably never relinquish that distinction,” said Brookes.

“Nothing escaped the camera in Vietnam. Between civilian and military photographers, millions of photographs and miles of film footage were taken. The government and military wanted to document the war, bolster home support, and propagandise the noble effort it was making in the name of stopping communism in its tracks in southeast Asia. What better tool than the camera?

“It failed, in both its public relations effort and the war itself. Instead, the camera helped kill the war.

“By the time the government and military figured out that the unbridled freedom they naively had given the media to support their propaganda effort had woefully backfired, it was too late.

“The images of the war that became icons of the horror and brutality that was Vietnam had fuelled an unstoppable anti-war movement. Instead of rallying the public to support the noble effort, it turned them against it. Pictures like those taken by the war’s civilian press photographers – Nick Ut’s ‘Napalm Girl’ and Eddie Adams’ photograph of the execution of a Viet Cong prisoner in a Saigon street, for instance – combined with those of military photographer Ron Haeberle of the My Lai massacre of Vietnamese civilians by American troops, were never anticipated.

“In Vietnam, truth finally triumphed over propaganda.”

Arguably the most controversial war in the United States’ history, Vietnam continues to spark fiery debate nearly 50 years after the USA pulled its troops out of the south east Asian country – was it a country bravely standing up against the tyranny of communist oppression or was it reclusive superpower foisting its own philosophies on an aspiring country half a world away? A Cold War battleground between the clashing ideologies of the USSR (communism) and the USA (capitalism), the war was first and foremost between the communist north of Vietnam and the government of South Vietnam which saw millions of people slaughtered. Estimates suggest 2 million civilians perished across the north and south, as well as 1.1 million Viet Cong/communists, approximately 250,000 South Vietnamese, and over 58,000 US troops. By 1969, the United States had over 500,000 soldiers on the ground in Vietnam.

The war was not popular. Huge protests regularly took place in the United States as people draft-dodged and held huge anti-war rallies in universities and protests across the country – still feeling the effects of the Second World War and the Korean War, every dead soldier fuelled the peace process.

Supposedly a tool for publicity relations, photographers in Vietnam were originally given carte blanche to photograph what they wanted. The results were rarely positive for the US government.

“Many of the greatest images of the Vietnam War, the most photographed war ever, came from the lenses of a long list of civilian shooters. Horst Faas, Henri Huet, Larry Burrows, and their numerous colleagues produced some of the finest war photographs ever,” explained Brookes.

“But behind the scenes, and unheralded for their camera work, were hundreds of military photographers, just doing what was expected of them as a part of their day-to-day job description. Unlike their famous civilian counterparts, many had to endure a year-long assignment that constantly placed them in harm’s way. Sometimes it meant dropping the camera and picking up an M-16 or grenade launcher, or manning an M-60 machine gun, or helping to carry the wounded to a medevac dust-off chopper.

“From 1962 to 1975, military photographers took millions of photographs in Vietnam. Their official mission was to document the war and capture images for the historical record. But more often, their cameras recorded the lives of their fellow soldiers in a sort of self-initiated public relations effort. They photographed the everyday activities in and out of combat, the struggles to cope with the conditions in the field, the battles with a mostly unseen enemy, booby traps, helicopter evacuations of the wounded and dead; anything and everything that went on in the war.”

effect on the enemy in a war which saw millions slaughtered. Mediadrumworld/DanBrookes/BobHillerby/PenAndSwordBooks

Many of the greatest war photographers sought to show the truth of war – its horror, suffering, desperation, and hopelessness. They captured everything that was terrible about war and placed it “squarely in the public eye”.

One particularly horrifying photograph captures the terror in the faces of civilians, seconds before they were brutally murdered. The heart-wrenching photo, which eventually saw far tighter restrictions placed on US military photographers, was taken by Army combat photographer Ronald Haeberle in 1968.

Heading to My Lai to capture some action shots of the US military before his tour finished, Haeberle jumped on a helicopter to head to the front line to check out reports of Viet Cong amassing in the area. When they landed, the photographer saw that his comrades had opened fire on a group of Vietnamese people on a trail heading into a local village.

“I’d seen Vietnamese people with their goods on their back, you know, that’s their normal way of going to market in the morning, and all of a sudden the GIs open up on them,” explained Haeberle, in a previous interview in the 1980s.

“When we got to the bodies we could see they were nothing but civilians. I started to take pictures.”

Haeberle then described the circumstances of the photograph he took – showing the tearful local people trying to protect themselves. He came upon the women and children, surrounded by some GIs. One woman was trying to button up her blouse after one of the soldiers had tried to rip it off. As he raised his Nikon, a GI shouted, “Whoa, whoa!”

He took the photograph, turned around and started to walk away.

“All of a sudden, ‘Bam, bam, bam, bam!’ and I look around and there’s all these people going down,” finished Haeberle.

The sickened photographer handed the photos over to his superiors to ensure the men responsible were brought to justice. In a bizarre twist of fate, the photographer himself ended up being charged himself for suppressing photographic evidence.

Another breath-taking account of an under fire photographer’s mission – and its thanklessness – comes from acclaimed combat journalist Joe Galloway, summing up his most frightening experience whilst working alongside the stoic photographers.

“On the worst day of my life, in the bloodiest battle of the war, on November 15 1965, in Landing Zone XRay in the Ia Drang Valley, we were surrounded by North Vietnamese regulars determined to kill us all,” recalled Galloway.

“The air was filled with bullets and shrapnel and I was hugging the earth. Out of the corner of my eye I noticed two men with cameras nearby, also hugging the ground. Later, during a lull in the fighting, I saw them filming the battalion surgeon, Dr Robert Carrera, as he did an urgent tracheotomy on a badly wounded soldier.

“The two of them, Sergeant Jack Yamaguchi and Sergeant Thomas Schiro, were from the Department of the Army Special Photographic Office (DASPO). Their film would be shipped back to the Pentagon, edited and released to the networks. They had risked their lives and captured priceless film of a historic battle.

“You might expect they would win some praise; maybe another stripe. Hardly. Their bosses in the Pentagon reprimanded Yamaguchi and Schiro for portraying so grim and bloody a story.”

The life and times of a military combat photographer in the most photographed war in history are often depressing, frequently moving, but always enthralling.

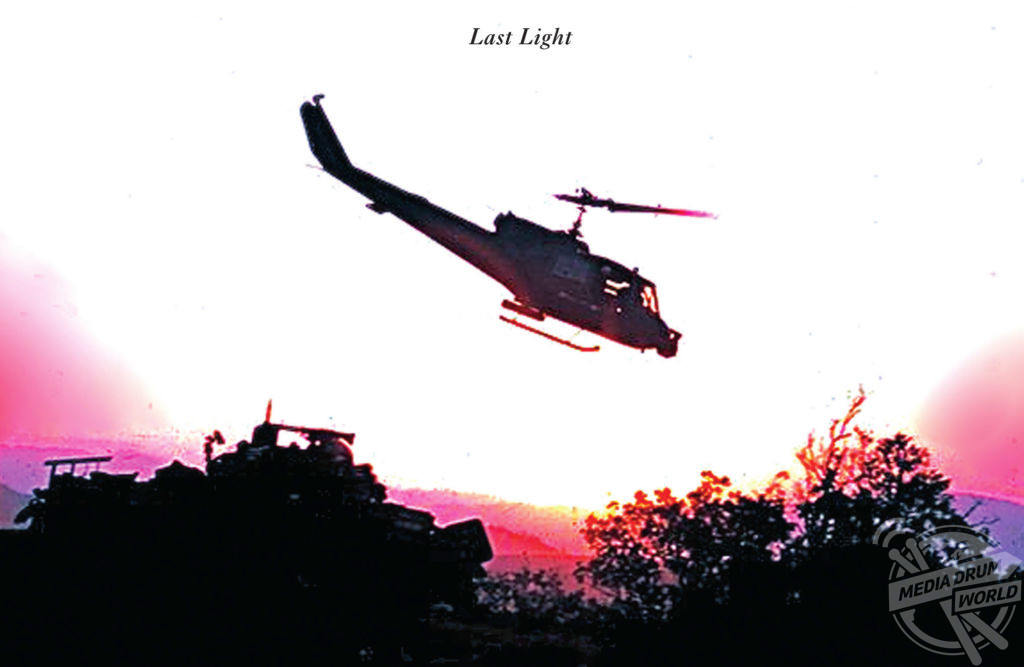

a “last light” mission, allowing them to check for enemy movements with less chance of reprisal. Mediadrumworld/DanBrookes/BobHillerby/PenAndSwordBooks

“There have been other books with hundreds of photographs of the Vietnam War, but for the most part, they concentrated on the images. We wanted you not just to see the war through the cameras of the photographers in these pages – we wanted you to experience their thoughts and emotions as well, to share their hardships and dedication to duty in documenting a war like no other,” said Brookes on behalf of his co-author Hillerby, who sadly passed away before their book could be published.

“They seldom, if ever, saw any of the praise or adulation that was heaped upon their civilian counterparts. Most just quietly went about their assigned duties. Some were lucky enough to get an occasional byline for a photo seen in the [military newspaper] Stars and Stripes or back in a hometown newspaper; most got no more than a now-faded purple caption along with their name on the back of a photograph buried among thousands of others in our National Archives.

“Just as most of us in Vietnam came to fight for each other and not some ill-defined political goal, the combat photographers of all branches of the military, if only in some small way, made those on the other side of the cameras feel important enough to have themselves and what they endured captured in images that will be forever preserved.”

Dan Brookes & Bob Hillerby’s new book Shooting Vietnam: Reflections on the War by Its Military Photographers, published by Pen And Sword books, is due for release at the end of the month.