By Alex Jones

REMARKABLE vintage photos show the animals which served during the First World War – including the bear which went on to inspire a beloved series of children’s books.

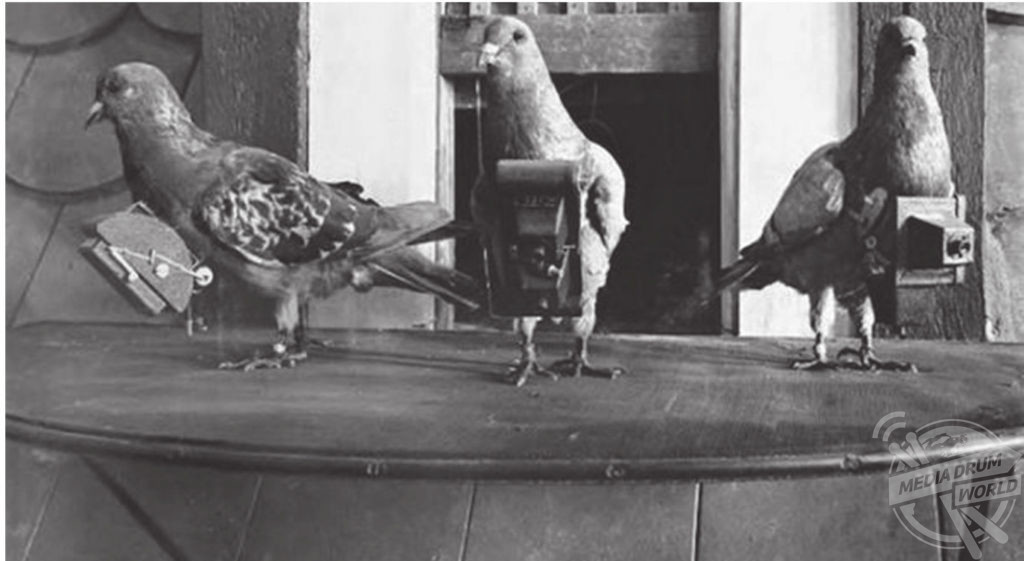

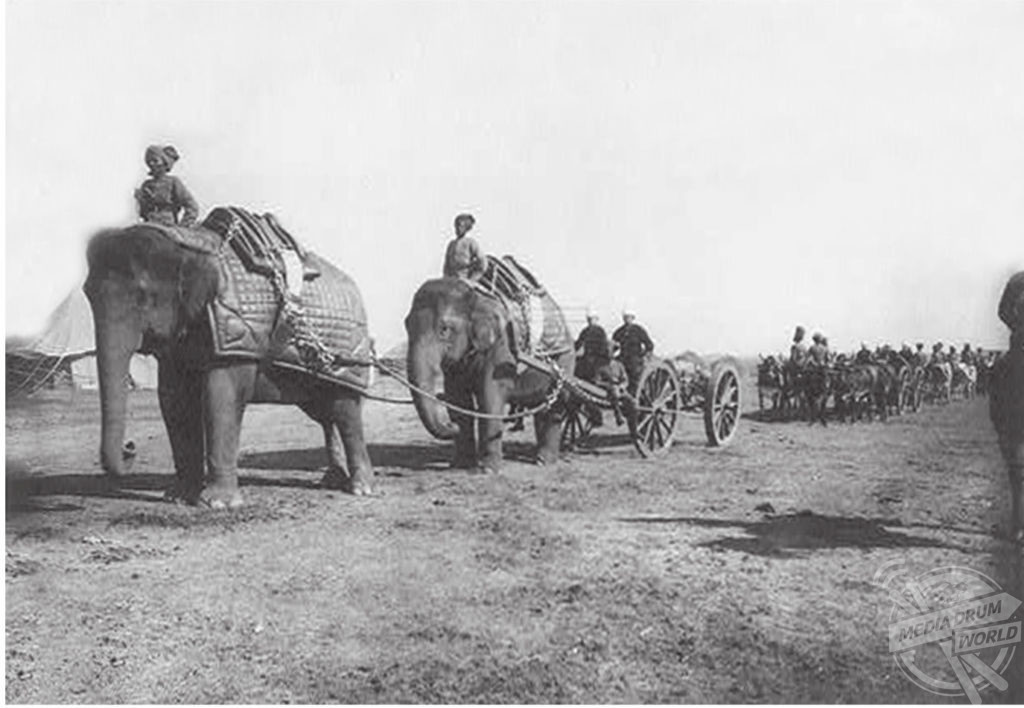

Spy pigeons carrying cameras, elephants pulling huge cannons, and a kangaroo at the foot of the Great Pyramids.

These are just some of the incredible images included in Tanya and Stephen Wynn’s latest book Animals in the Great War, a fascinating look at the use of animals by all sides in the Great War and the effect they had.

“Animals and war have gone hand in hand for thousands of years,” explained the authors.

“The earliest evidence of horses being used in warfare dates back to Eurasia, sometime between 4000 and 3000 BC. The years between 1600 and 1350 BC saw the use of horse drawn chariots throughout the area which roughly covers what is known as the Middle East today. The earliest use of saddles on horses, or what then passed for saddles, can be traced to around 700 BC by Assyrian cavalry.

“There were many different types of animals used in the First World War, horses certainly weren’t the only ones that were used. Donkeys and asses were used to convey artillery pieces, ammunition and other equipment to and from the front line. Dogs, cats and pigeons were employed for different military purposes, and others, such as a springbok of the 4th South African Regiment, were used as mascots.”

Over 16 million animals served in the First World War. They were used for transport, communication and companionship. Horses, donkeys, mules and camels carried food, water, ammunition and medical supplies to men at the front, and dogs and pigeons carried messages. Birds, typically canaries, were used to detect poisonous gas, and cats and dogs were trained to hunt rats in the trenches and wounded men in No Man’s Land.

Although animals have been sacrificed in conflict for centuries, if not millennia, never was the spilling of military animal blood more pronounced than during the four-and-a-half years of the First World War, where it is estimated that 8 million horses, mules and donkeys died, along with 100,000 pigeons.

In the early years of the war, horses were, to a large extent, the only form of transport that was available to the British Army, ranging from use by cavalry units, artillery units as well others such as the Army Ordnance Corps for the conveying of ammunition supplies to men fighting at the front. Britain sent an estimated one million horses to fight in the war, most of them to France and Belgium, but only 60,000 of them ever returned home, and only then were they returned because of the intervention of Winston Churchill.

But equine associates were far from the only feathered and furry friends to play their part in the deadly conflict.

“Pigeons were possibly more widely used than was actually appreciated,” added Tanya and Stephen Wynn.

“Most people think of them flying about in the trenches on the Western Front, sending vital messages all over the place, which they did, but they were also used from on board ships. If a vessel of the British Royal Navy was in a battle on the high seas, the chances were that the ship’s radio operator would have sufficient time to get off a message, but if they suffered a surprise attack by a German submarine, the only option for the crew of a quickly sinking ship might have been to send a messenger pigeon. Armed with the details of their last position at the time of their sinking, a pigeon might mean the difference between life and death for any crew.”

More unusual animals were involved too. The aforementioned elephants would pull and haul heavy artillery pieces all day long for Indian soldiers fighting in the war, often over ground that any other vehicle or animal would struggle with. Flying foxes, noble goats and well-travelled kangaroos notably served as mascots for various units and were well tended to by the troops responsible for them.

In particularly striking passage, the authors explain how the impromptu purchase of a bear by a Canadian soldier sparked the creation of one of Britain’s favourite literary characters.

“At the outbreak of the First World War, Harry D. Colebourn was a lieutenant in the Fort Garry Horse, which was a Canadian cavalry regiment,” explained the writing partners.

“He quickly volunteered for service and enlisted in the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps. On his way to the Valcartier forces’ base, which is about 15 miles north of Quebec City, the train he was on stopped at White River, Ontario. Whilst there, Colebourn possibly did the most unusual thing anybody who was en route to join up with his new military unit could have possibly done. He purchased a bear. He purchased a small, black, female bear from a hunter for $20. As the young bear had constantly been with humans for nearly all of her young life, she was already domesticated in the art of human interaction. Colebourn decided on the name Winnipeg, which in turn was quickly shortened to Winnie, after his hometown of Winnipeg in Manitoba.

“After much discussion with his recruiters Colebourn was somehow allowed to keep the bear, and it became the official mascot of the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps. The bear would soon travel to Britain with him.

“When Colebourn had to leave England on his way to France as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, he knew that it simply was not practicable to take Winnie with him, so he arranged for her to stay at London Zoo, who were more than happy to look after her. After the war, Colebourn fully intended to take Winnie back to Canada with him, where he meant for her to see out her days at the Assiniboine Park Zoo, in his hometown of Winnipeg, but when Colebourn discovered how happy she was at London Zoo, and that she had become a much-loved attraction because of her playful and gentle manner, he changed his mind, and decided it was better for Winnie to remain where she was. She died at London Zoo on 12 May 1934, when she was 20 years of age.

“So the story goes, that whilst Winnie was staying at London Zoo, the famous writer, Mr A.A. Milne, took his son, Christopher Robin, to see her. He was so taken by her that his father started writing stories about his son and Winnipeg, which subsequently became the now world-famous Winnie the Pooh stories.”

Another startling tale involved a brutish and unfortunately named pooch in war time France.

“In the early months of the war, a loving little dog who had somehow acquired the unfortunate name of Ugly, arrived in France,” continued the Wynns.

“Not as one might think, an official, well-groomed military dog of the British Army, but as an unowned, scruffy and unkempt-looking mongrel. He had been a stowaway on a Channel Packet. If his scars and scratches were anything to go by, he had certainly been used to fighting, that was for sure.

“He became attached to the Army Service Corps (Pickford’s Light Horse) and made his name catching rats. So successful was he at reducing the rats’ numbers that he was rewarded with a promotion to the rank of corporal and double rations. He also found himself in several fights with stray French dogs who had wandered into his newly acquired territory, which he wasn’t about to give up so readily. In fact, Ugly had gained such a reputation for his fighting prowess, it had come to the notice of men fighting in the front-line trenches. Before long a letter was received from another British unit who claimed to have the ‘ugliest dog and the fiercest fighter in Flanders’ and gambled £5 that their mascot would win in a scrap. The challenge was accepted and Ugly was put into strict training, much to his disgust. He was put on an exclusive diet of bully beef and biscuit to harden his teeth and augment his angry passions.

“A heavy book was made on the fight, and when the eagerly anticipated evening of the doggy duel finally arrived, the selected location was packed with a keen and expectant crowd. Ugly was ready and waiting, striding up and down like an expectant father showing everybody present that he was the daddy. By now, both dogs had caught each other’s scents and the growling and gnashing of teeth began. [Opponent canine fighter] Sergeant Smiler also looked fierce and the two dogs were soon engaged in their own interpretation of a Mexican stand-off.

“Ugly began his routine first, like a Sumo wrestler, preparing to do battle. With his back hair bristling he crouched as if ready to spring into action, teeth bared and gums raised, as he psyched himself up, ready for the attack. But then, the unthinkable happened – he sat down, smiled and wagged his tail. As he glanced across at his opponent, he was confronted with his complete double, in size, shape and colour. Sergeant Smiler also crouched, lying on the ground as if he was frozen to the spot. Both dogs stared at each other quizzically, each recognising the other.

his time on the Western Front he was wounded twice. Mediadrumimages/TanyaWynn/StephenWynn/PenAndSwordBooks

“Without warning, the dogs launched at each other, but there was no biting and scratching, just joyful tail wagging and excited yaps as they tussled and mouthed each other’s necks. It was evident to all present that despite their bets and wishes, there was to be no fight, not even a bite or a scratch. It was more like a love-in as two long lost friends met for the first time in years. As it turned out Corporal Ugly and Sergeant Smiler were brothers from the same litter, separated as puppies, who had pursued different paths, only to meet up again on the Western Front in war-time France.

“Truth is sometimes stranger than fiction, and despite any doubts you might have about the authenticity of this story, it is in fact true.”

Tanya and Stephen Wynn’s Animals in the Great War, published by Pen and Sword Books, is to be released on 31 May. Preorder here.