By Alex Jones

ONE HUNDRED years ago two brave British World War veterans crash-landed into history by becoming the first people to fly across the Atlantic Ocean nonstop.

Although history typically remembers US aviator Charles Lindbergh as the first man to fly from North America to Europe, in reality he was beaten to the record by Manchester-born Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Brown by eight whole years in 1919.

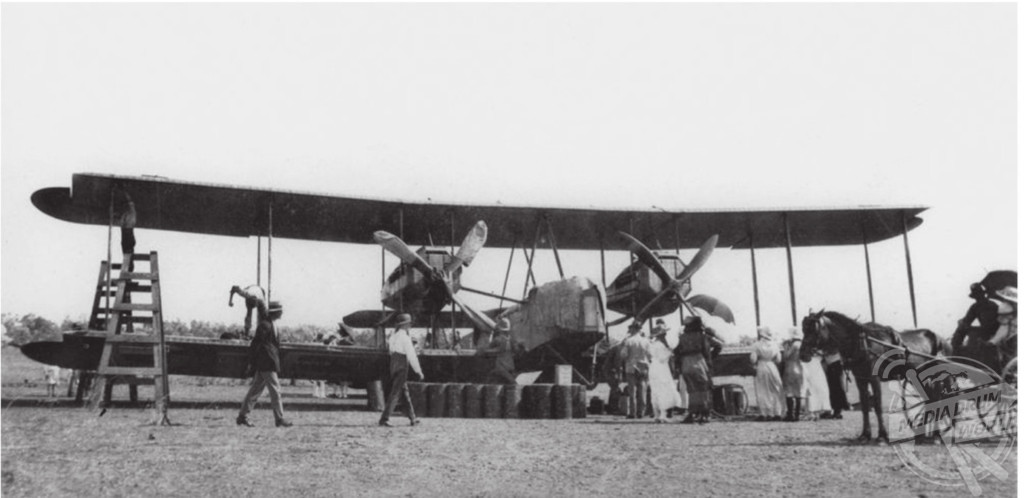

Remarkable photos show the pair’s rudimentary plane’s nose buried in an Irish bog after the winged contraption only just reached land after their epic crossing, the two pioneers nervously nibbling their last meal in North America before starting their world-record attempt, and the very first mailbag to fly across the Atlantic without pause.

The stunning photos are included in Bruce Vigar and Colin Higgs’ new book Race Across the Atlantic: Alcock and Brown’s Record-Breaking Non-Stop Flight, an enthralling account of the death-defying 16-and-a-half-hour flight through terrible weather on 14/15 June 1919.

“It could have been another April Fool prank, when at the beginning of April 1913 Lord Rothermere, aviation philanthropist and owner of the Daily Mail, offered a prize of £10,000, roughly equivalent to £1million in today’s money, to ‘the aviator who shall first cross the Atlantic in an aeroplane in flight from any point in the United States of America, Canada or Newfoundland to any point in Great Britain or Ireland in 72 continuous hours’,” explained the authors.

“Fifty years ago, man landed on the moon and Concorde flew for the first time. It seemed that there were few boundaries that human ingenuity, inventiveness and curiosity could not overcome.

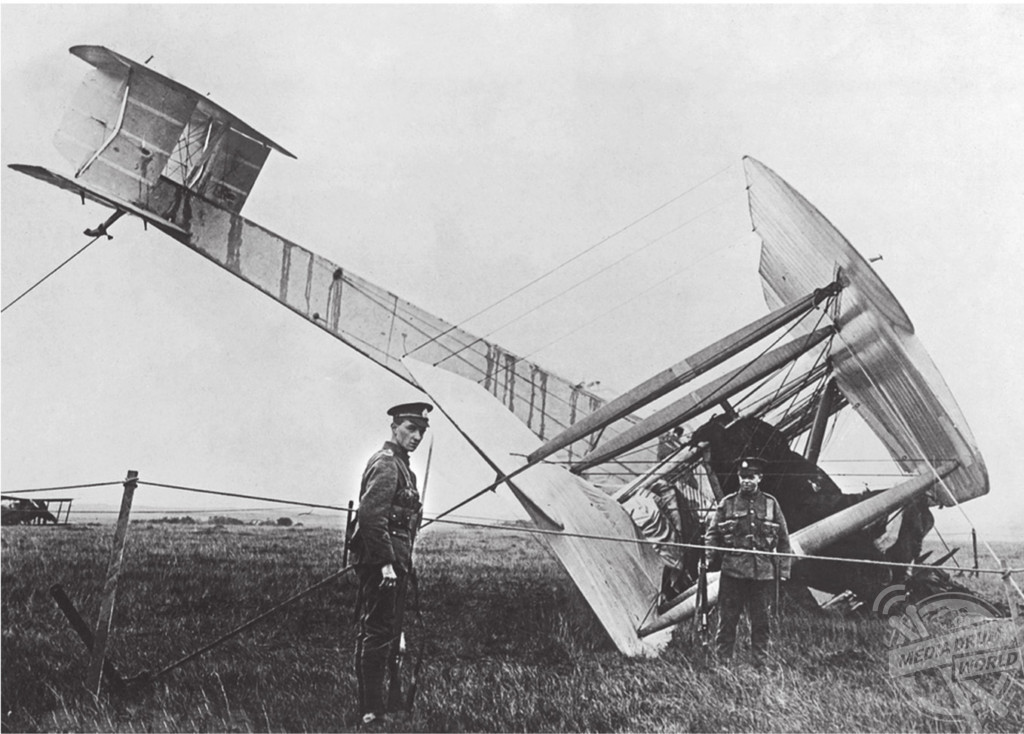

“Those words could have been the headlines in 1919 when on 15 June Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Whitten Brown crash-landed their Vickers Vimy aircraft into a bog in western Ireland.

“Their achievement was as massive a step forward in aviation.

“In just ten years, aircraft that could barely cross the English Channel could now fly 1,900 miles across the Atlantic Ocean.

“The world needed new horizons and inspiration, a ‘fresh start’ after the numbing devastation of the First World War and the deadly flu epidemic that followed.

“It was as if mankind had turned a corner and that aviation would bring people together, inhabitants of a ‘global village’ in which disputes and misunderstandings could be overcome by talking face to face.

“Where Alcock and Brown led, others soon followed. A month after their flight, the R-34 Airship made the first east to west crossing in just over four days.

“After several days of celebrations, receptions and re-equipping, R-34 made the return crossing.

“It was another eight years before the first solo crossing by Charles Lindbergh. Arguably his achievement has eclipsed that of Alcock and Brown in some quarters, but as he stepped out of his small aeroplane at Le Bourget in Paris, he acknowledged Alcock and Brown’s achievement with the words: ‘Alcock and Brown showed me the way.’”

The 15th of June 100 years ago would prove a fateful day for the residents of Clifden on Ireland’s west coast and for aviation history.

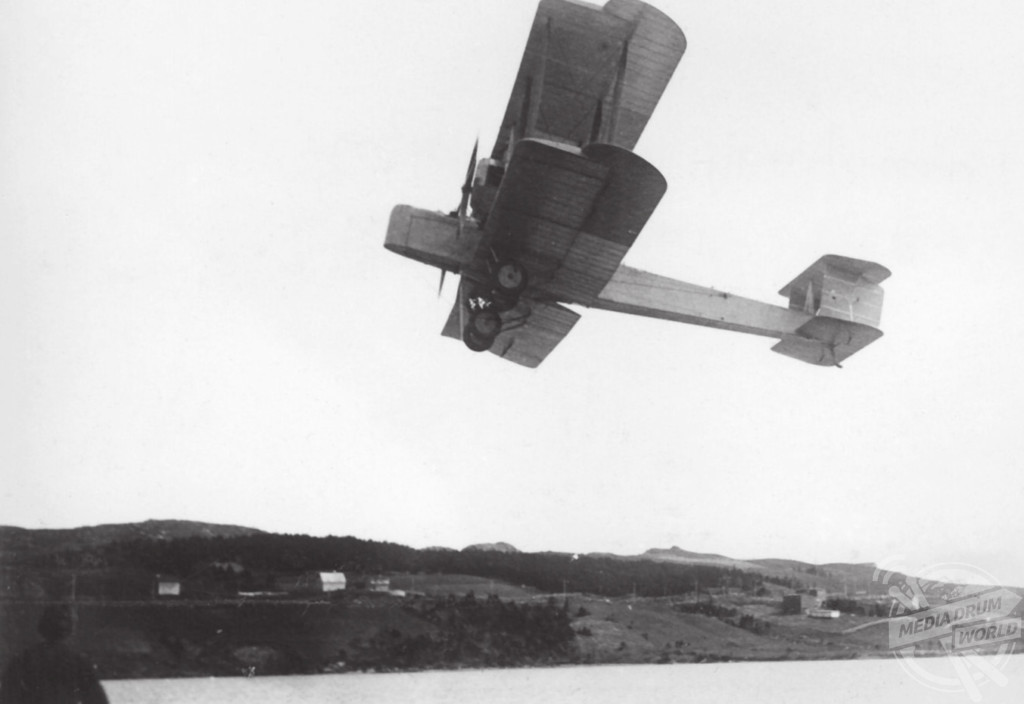

Just before 9am, descending out of the gloom, came a large, twin-engine aeroplane lining up for final approach. One or two on-lookers recognised the danger straight away for this was an area of soft bog, but their attempts to alert the pilot were in vain.

The aircraft began to sink and, with a squelch, came to a sudden stop, the tail rearing up in the air. Dazed and with fuel filling the cockpit the two-man crew scrambled out, grabbing what they could. After a flight lasting 16 hours and 28 minutes, Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten-Brown had won the race to be the first to fly non-stop across the Atlantic.

Race Across the Atlantic also includes a first-hand account from Captain Brown of his world-first flight.

“We have had a terrible journey,” he admitted, in a Daily Mail report in the days after landing in Ireland.

“The wonder is that we are here at all.

“We scarcely saw the sun or the moon or the stars. For hours we saw none of them. The fog was very dense, and at times we had to descend to within 300 feet of the sea.

“For four hours the machine was covered in a sheet of ice caused by frozen sleet; at another time the sleet was so dense and for a few seconds my speed indicator did not work, and for a few seconds it was very alarming.

“The winds were favourable all the way: north-west and at times, south-west. We said in Newfoundland we would do the trip in sixteen hours, but never thought we should. An hour and a half before we saw land we had no certain idea of where we were, but we believed we were at Galway or thereabouts.

“Our delight in seeing Eeshal Island and Turbot Island was great.

“We drank coffee and ale and ate sandwiches and chocolate.

“The only thing that upset me was to see the machine at the end get damaged. From above, the bog looked like a lovely field, but the machine sank into it up to the axle and fell over on to her nose.”

Alcock and Brown would soon be presented with a cheque for £10,000 by none other than Winston Churchill.Vigar and Higg’s new book, illustrated by many unique photographs, tells the story of the race, delayed for almost six years by the First World War.

Many aircraft would be entered but few would even get off the ground. People lost their lives. The teams faced great difficulties in preparing for the challenge of crossing one of the most hostile stretches of ocean on Earth.

The authors not only reveal tales of failures and technical difficulties, but of the intense frustration of waiting for the perfect weather-window. And even when finally airborne, Alcock and Brown’s flight almost ended in disaster on several occasions as weather conditions almost conspired to cast them down into the grey, cold waters of the Atlantic and almost certain death. At one point they were less than 20 feet above the vast ocean.

Their radio also broke just a few hours into their troubled flight. Had they crashed into the sea, they would have had no way of contacting anyone to report their position or request assistance.

The book also explores the lives of Alcock – who spent 14 months as a prisoner of war devising his trans-Atlantic plans – and Brown – who had taught himself to navigate by reading books – and the remarkable turns of fate that allowed them to crash-land into the record books.

The early 20th Century was a brave new world for pioneer aviators, who would risk their lives every time they got in their prototype planes.

Just 100 years after Alcock and Brown’s historic flight, it’s perhaps too easy to take the comfort of international travel for granted.

“1919 was a ‘Golden Year’ in the story of flight,” added Vigar and Higgs.

“It was a year of progress and achievement of global significance that touched the lives of millions around the world beyond the world of aviation.”

Bruce Vigar and Colin Higgs’ Race Across the Atlantic: Alcock and Brown’s Record-Breaking Non-Stop Flight, published by Pen and Sword Books, is set for release next month. It can be preordered here.